Evidence #106 | November 2, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Comparing Contemporary Authors

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

When compared to the needed preparations involved on the part of several prominent 19th-century authors to create their literary masterpieces, Joseph Smith seems to have been considerably underprepared to create a text like the Book of Mormon.Since its publication in 1830, a variety of theories have surfaced which compete with Joseph Smith’s claim that he translated the Book of Mormon by the gift and power of God. Several such theories have proposed that one or more individuals other than Joseph was primarily responsible for the book’s authorship. However, such proposals are typically abundant in speculation and sparse, if not completely lacking, in historically supportable evidence. For this reason, the most popular alternative theory today assumes that Joseph himself created (rather than translated) the Book of Mormon using his own literary talents.1

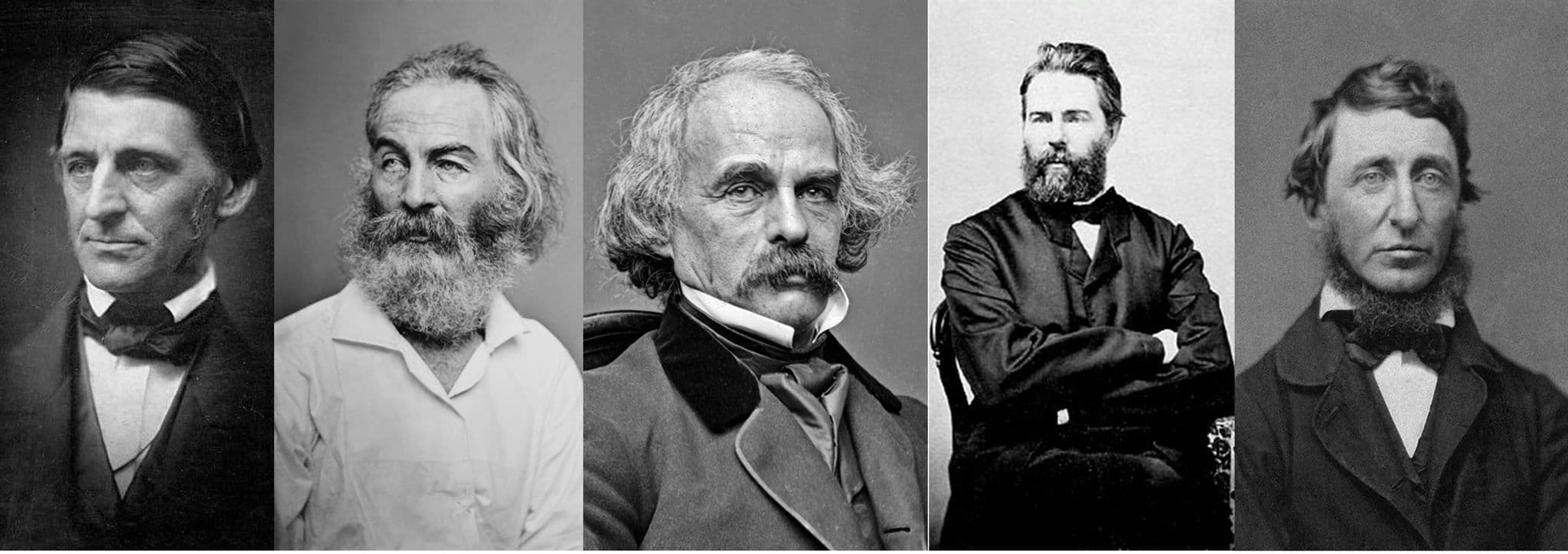

To help assess the merits of in this theory, literary scholar Robert A. Rees has carried out studies comparing Joseph Smith’s production of the Book of Mormon to the conditions and preparation needed for some of the greatest American authors of the 19th century—namely Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman—to produce their own literary masterpieces.2

Education

Rees notes that in contrast to Joseph Smith, each of the acclaimed Romantic-era American authors had superior educational opportunities. Emerson received an excellent education at the Boston Latin School and Harvard College. Thoreau attended the Concord Academy and also went to Harvard College. At age seventeen, Hawthorne entered Bowdoin College, from which he graduated. Melville attended the “New York Male School, Lansingburgh Academy, the Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School, and Albany Academy.”3 And Whitman, although he was taken out of formal schooling at age eleven, began at that time to work “in printing, journalism, and the various trades he pursued during his lifetime.”4

In contrast, Joseph Smith’s educational experience was quite dismal. He may have had the opportunity to attend as many as seven years of formal schooling,5 but whether or not he actually did attend school during those years is unknown. What is certain is that virtually every relevant report from those who knew Joseph in the years surrounding 1829 describes him as relatively unlearned and lacking in education. Analysis of Joseph’s personal writings near that time are consistent with such descriptions.6

Environment

The prominent Romantic-era authors were typically surrounded by people and circumstances that helped facilitate their literary talents. As explained by Rees,

Emerson lived in one of the most creative and intellectually stimulating environments in American history. He was at the center of an amazing array of poets, artists, philosophers, educators, innovators, explorers, adventurers, and other luminaries. He was heralded not only in America but in Europe, where he met other writers who influenced him—people like Wordsworth, Coleridge, Eliot, and Carlyle.7

The other authors had similar associations. “Thoreau lived for a time in Emerson’s house and tutored Emerson’s … children. He enjoyed the association of a number of other writers and thinkers, including Hawthorne and Whitman.”8 Hawthorne “served as US Ambassador to Liverpool for four years (1853–57) during which time he interacted with distinguished British writers” and his wife Sophia Peabody proved to be “an excellent critic and editor of her husband’s works.”9 Melville had a close relationship with Hawthorne and gained much experience from his travels abroad. And Whitman, who as mentioned above had association with Thoreau, “worked as a nurse in a military hospital in Washington, D.C.,” and “was employed at several federal agencies.”10

As summarized by Rees, “all were intimately involved in the cultural life of their communities, attending lyceums and concerts, lecturing, publishing and, with the exception of Thoreau (who said that he had traveled much in Concord), traveling far beyond their local environs.”11 In contrast, nothing from Joseph Smith’s formative years appears to have been particularly conducive to refining his literary capacities. According to his own account, he primarily spent his time in manual labor, trying to help his poor family make ends meet.12

Development as a Writer

Each of the acclaimed Romantic-era authors engaged in what Rees calls “try works”—preliminary literary efforts which helped the authors develop and refine their personal styles and native talents. Significantly, such efforts are absent in the historical record of Joseph Smith’s formative years. Rees asks,

Where are the “try works” of the Book of Mormon? There are none that we know of or evidence that there might have been. In other words—and this is important — whereas we see copious journal entries, essays, letters, lectures, and other writings revealing Emerson working out his mature expressions in poetry and prose; whereas we see Hawthorne’s significant volume of early fiction (short and long forms), journals, and other writings leading up to and illuminating the writing of The Scarlet Letter; whereas we see Thoreau’s copious journals, notebooks, essays, lectures, fields notes, and other writings as preludes to Walden; whereas we see Melville’s many novels, stories, and other writings preparing him to write Moby-Dick; and whereas as we see Whitman’s journalistic writings, poetry, and numerous drafts of his major poem Leaves of Grass, we have practically nothing of Joseph Smith’s mind or writing to suggest that he was capable of authoring a book like the Book of Mormon, a book that is much more substantial, complex, and varied than his critics have been able to see or willing to admit. We need to remember that the Book of Mormon is considered one of the most influential books in American history and one that has occupied the serious consideration of scholars for over a century.13

This point is especially noteworthy because the Book of Mormon is, by almost any measure, the most ambitious literary project that Joseph Smith undertook during his lifetime. It is the lengthiest, most elaborate, and most literarily complex of his claimed revelations. And yet, like lightening striking out of a clear blue sky, its words rolled forth from the Prophet’s mouth day after day between April 7 and June 30, 1829 without any prior hint that he was capable of creating such a text.14

Even if Joseph had the interest and ability needed to carry out such preparations, it appears he simply didn’t have the time. After outlining the many constraints that were placed on Joseph’s available time, Rees explains, “the idea that Joseph had time to read broadly, undertake research, construct various drafts, and work out the plot, characters, settings, various points of view, and multiple rhetorical styles that constitute the five-hundred-plus page narrative of the Book of Mormon is simply incredible (in its original Latin sense of ‘not worthy of belief’).”15

Conclusion

Comparing Joseph Smith to these acclaimed Romantic-era authors does not, on its own, prove that he couldn’t have created the contents of the Book of Mormon. But it does help demonstrate that the text’s production is unusual and unexpected coming from someone in Joseph Smith’s situation. As Rees concluded,

Each of the writers of each of the masterpieces under consideration here, with the exception of Joseph Smith, had a long gestation period during which he “tried out” his ideas, metaphors, allusions, coloring (tone), points of view, personae, and rhetorical styles before tackling a larger, more complex, and more sophisticated form, whether as a collection of poems and essays (Emerson), an extended personal narrative (Thoreau), a novel (Hawthorne and Melville) or a major poem (Whitman). There are no parallel try works for Joseph Smith, nor any evidence of his apprenticeship as a writer. In fact, all evidence points in the opposite direction. Unless and until some hitherto undiscovered record demonstrating that Joseph Smith did in fact leave evidence of the reading, thinking, writing, and imaginative expression—the try works—required to write a book like the Book of Mormon, we are left with the choice of accepting his explanation of the book’s origin or making the case for some alternative explanation, which to my mind no one has done satisfactorily.16

Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance: An Update,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 19 (2016): 1–16.

Robert A. Rees, “John Milton, Joseph Smith, and the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2015): 6–18.

Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 3 (2002): 83–112.

- 1. For several overviews of these alternative theories, the history of their popularity, and their inherent limitations, see Brian C. Hales, “Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study,” BYU Studies Quarterly 58, no. 3 (2019): 105–148; Daniel C. Peterson, “Editor’s Introduction: ‘In the Hope That Something Will Stick’: Changing Explanations for the Book of Mormon,” FARMS Review 16, no. 2 (2004): xi-xxxv; Daniel C. Peterson, “The Divine Source of the Book of Mormon in the Face of Alternative Theories Advocated by LDS Critics,” 2001 FairMormon Conference Presentation, online at archive.bookofmormoncentral.org; Louis Midgley, “Who Really Wrote the Book of Mormon? The Critics and Their Theories,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1997), 101–139.

- 2. See Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 3 (2002): 83–112; Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance: An Update,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 19 (2016): 1–16. For a related study, see Robert A. Rees, “John Milton, Joseph Smith, and the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2015): 6–18.

- 3. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 7.

- 4. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 8.

- 5. See William Davis, “Reassessing Joseph Smith, Jr.’s Formal Education,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 49, no. 4 (2016): 46.

- 6. For a summary of these points, see Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Joseph Smith’s Limited Education,” September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org. See also Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 3 (2002): 95–97.

- 7. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 6.

- 8. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 6.

- 9. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 7.

- 10. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 9.

- 11. Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance,” 95.

- 12. See Letterbook 1, p. 1, accessed August 28, 2020, online at josephsmithpapers.org: “at the age of about ten years my Father Joseph Smith Seignior moved to Palmyra Ontario County in the State of New York and being in indigent circumstances were obliged to labour hard for the support of a large Family having nine chilldren and as it required the exertions of all that were able to render any assistance for the support of the Family therefore we were deprived of the bennifit of an education suffice it to say I was mearly instructtid in reading writing and the ground rules of Arithmatic which constituted my whole literary acquirements” (editing marks removed, but original spelling retained).

- 13. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 12.

- 14. Joseph Smith’s 1828 efforts to translate the Book of Mormon can’t really count as prior literary experience because the lost manuscript pages, if we had them today, are purportedly part of the very text whose origins and productions are being disputed. Moreover, each side of the debate can only speculate as to what its contents would have looked like. Would it have looked like a “try work”—a preliminary effort to work out the Book of Mormon’s major plots or themes? Or would it manifest the same degree of complexity and consistency and final polish that we find in the portions of the text that were translated in spring and summer of 1829? The evidence simply isn’t available for analysis. For an exploration of what may have been on the lost 116 pages, see Don Bradley, The Lost 116 Pages: Reconstructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2019); Book of Mormon Central, “What Was on the Lost 116 Pages? (1 Nephi 9:5),” KnoWhy 452 (July 24, 2018).

- 15. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 11.

- 16. Rees, “Joseph Smith … An Update,” 15–16.