April 2, 2019

What Translating Harry Potter Reveals About the Book of Mormon

Post contributed by

Stephen Smoot

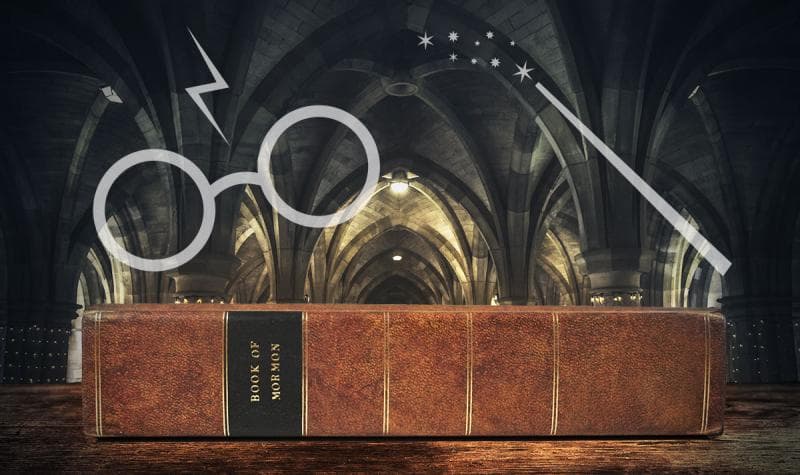

Easily some of the most beloved and popular books in recent memory, the Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling has charmed and captivated millions of fans around the world. English-speaking readers of the series, however, may take for granted the intense and sometimes frustrating task of translating the series into other languages. As the following video explains, the presence of English alliteration, puns, invented words, and cultural references peppered throughout the series posed a serious obstacle to translation into other languages.

As the video explains, some translators took considerable liberties in adapting the the Harry Potter books into the target language to better communicate the underlying meaning while others stayed fairly close to Rowling’s English. In some instances, character names were modified to capture the clever or subtle meaning packed into Rowling’s original names at the expense of preserving elements only detectable in English. In other cases, Rowling’s invented words were retained in English and set off by italics.

Translators also adapted cultural references into new ones that better suit the readers. Dumbledore’s favorite candy Sherbert lemons–––which are popular in Great Britain–––thus became the chocolate-covered marshmallow treat Krembo in Israel.

But what does any of this have to do with the Book of Mormon? As Joseph Smith affirmed throughout his life and ministry, the Book of Mormon is an inspired translation of an ancient record.1 Joseph did not accomplish this translation by ordinary scholarly means, but through the gift and power of God. While members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints affirm the Book of Mormon is a translation of an ancient record, several questions remain as to what kind of translation is the English text of the Nephite record. Is it a “literal” translation that sticks closely to the underlying text composed by the ancient Nephite prophets? Or does it include English-level adaptations by Joseph Smith, making it more of a “loose” translation? Or is it somewhere in-between?

Different Types of Translations

Book of Mormon scholars such as Royal Skousen and Brant Gardner, to name just two, have offered varying answers to this question based on many different strands of evidence.2 On the one hand, the presence of poetic parallelisms, word-level consistency, and distinctly separate authorship styles, provide evidence that some parts of the translation may have been quite literal. The presence of Early Modern English language likewise makes attributing authorship to Joseph Smith problematic. On the other hand, quotations of King James Bible passages as well as nineteenth century Christianized language (such as “Bible,” “church,” “apostle,” “Christ,” and so forth) hints that the translation, at least on some level, was likely adapted by Joseph Smith for a modern Christian audience.

Translating Book of Mormon Cultural References

The rendering of the names of animals has long vexed translators of the Bible.3 So too have biblical idioms. How, for example, does a translator make a phrase like “lamb of God” intelligible to people in Greenland, where “culture and nature . . . in so many ways [are] quite different from the world of the Bible”? The answer, apparently, was to replace lamb with seal and compare sheep with native species such as caribou.4

Along similar lines, some have wondered if the seemingly-anachronistic animals mentioned in the Book of Mormon (such as horses) might actually be the result of Joseph Smith’s English translation. Similar to how translators of the Bible grapple with translating the names of animals, or how the King James Bible translators at times slipped into anachronistic language, “horses” in the Book of Mormon might be Joseph Smith’s rendering of the Nephite word for, perhaps, tapir or deer.5

Translating Book of Mormon Names

And what about names in the Book of Mormon? Some of the names found among the Jaredites include Israelite names such as Aaron and Levi (Ether 1:15–16, 20–21; 10:14–15, 31). But the Jaredites departed the Old World long before the children of Israel entered the historical scene. Whence these biblical names? Since the Book of Ether is Joseph Smith’s translation of Moroni’s abridgement of Mosiah’s translation of Ether’s abridgement of Jaredite oral and written sources, there is a real possibility that these names are the result of Mosiah’s translation, or Moroni’s abridgement of Mosiah’s translation, or Joseph Smith’s translation of Moroni’s abridgement of Mosiah’s translation of the Jaredite records!

Understanding the Nature of Translation

More examples could be cited, but the point I’m trying to make here is this: even if it is accomplished with the aid of divine inspiration, the translation of scripture (like the translation of the Harry Potter series) is still subject to real-world rules and barriers. Robert Alter has recently explored how the translation of an ancient text like the Bible into modern English is often a much more daunting task than many might suppose, involving not just properly rendering word choice, grammar, and syntax, but also the preservation of nuanced literary and linguistic elements.6

If the Book of Mormon is in fact a translation, as Latter-day Saints believe, then we should be sensitive to the fact that the same challenges which confront translators of the Bible or the Harry Potter series also confronted Joseph Smith. Otherwise, what do we do with the presence of non-translated words in the Book of Mormon such as ziff and, famously, the Jaredite animals cureloms and cumoms (Mosiah 11:3, 8; Ether 9:19)? Or with seemingly-anachronistic cultural and linguistic elements? If we assume divine translation entails an infallible and perfectly precise rendering of one language into another all the time and in all circumstances, then why does the Book of Mormon contain such?

The things discussed above are typically a feature, not a bug, when it comes to the nature of inspiration and revelation. After all, the Lord reveals truth “unto [His] servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding” (D&C 1:24). Or, as President Brigham Young taught,

When God speaks to the people, he does it in a manner to suit their circumstances and capacities. . . . Should the Lord Almighty send an angel to rewrite the Bible, it would in many places be very different from what it now is. And I will even venture to say that if the Book of Mormon were now to be rewritten, in many instances it would materially differ from the present translation. According as people are willing to receive the things of God, so the heavens send forth their blessings.7

The questions about the nature of the translation of the Book of Mormon raised above are certainly worth keeping in mind, but ultimately the best way to read the Book of Mormon is not to fret over currently-unanswerable questions about the translation, but to focus on its message of Jesus Christ and His gospel, knowing all the while that every sincere man and woman regardless of what language they read the book in can gain a testimony of its truthfulness through the gentle whisperings of the Spirit (Moroni 10:4–5).

Further Reading

- 1. See the overview in “Book of Mormon Translation,” Gospel Topics Essays, online at www.lds.org.

- 2. The work of Skousen and Gardner can be accessed for free on the Book of Mormon Central archive. See also Brant A. Gardner, The Gift and Power: Translating the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2011); Royal Skousen, “The Language of the Original Text of the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2018): 81–110.

- 3. See for instance the discussion in Edward R. Hope, “Animals in the Old Testament – Anybody’s Guess?” The Bible Translator 42, no. 1 (January 1991): 128–132.

- 4. Inge Kleivan, “‘Lamb of God’ = ‘Seal of God’: Some Semantic Problems in Translating the Animal Names of the New Testament into Greenlandic,” in Papers from the Fourth Scandinavian Conference of Linguistics, Hindsgavl, January 6-8, 1978, ed. Kirsten Gregersen (Odense: Odense University Press, 1978), 339–344.

- 5. Gardner, The Gift and Power, 235–239.

- 6. See Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Translation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

- 7. Brigham Young, “The Kingdom of God,” Journal of Discourses (July 13, 1862): 311.