Magazine

Side Lights on the Book of Mormon

Title

Side Lights on the Book of Mormon

Magazine

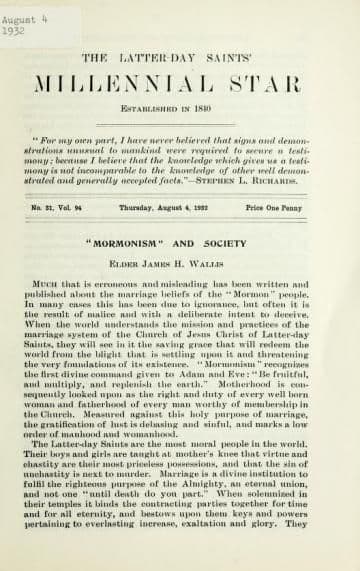

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1932

Authors

Evans, John Henry (Primary)

Pagination

490–495

Date Published

4 August 1932

Volume

94

Issue Number

31

Abstract

This article describes the experiences of some early converts to the Church—Thomas Marsh, Parley P. Pratt, Willard Richards, and others—who received their testimony from reading the Book of Mormon.

SIDE LIGHTS ON THE BOOK OF MORMON

Elder John Henry Evans

While the Book of Mormon was being set up at the printer’s in Palmyra, there came into the office one day a young man about thirty years old.

“I’m looking for someone,” he said, “who can give me some information about a book that was revealed by an angel and that is being printed here.”

Martin Harris happened to be in the printing office just then, and the stranger was referred to him.

“My name is Marsh,” the stranger explained—“Thomas B. Marsh. I was on my way from Charleston, Massachusetts, to my old home in New York, when I heard that an angel had appeared to one of your townsmen and made known to him a book of plates. What about it?”

Martin Harris took Marsh to the Smith home in Manchester, where they found Oliver Cowdery. Oliver told him the strange story, so that he got it firsthand.

Returning some time later to the printer’s, Marsh was given sixteen pages of the book that was to be. This he took home with him, reading it on the way and pondered over what he had been told. He believed what he had read and what he had been told about the book; and when he related the story to his wife and read to her the sixteen pages, she, too, believed.

Later Thomas B. Marsh, with his family, moved to New York, was baptized, and, when the first quorum of apostles was organized, became its president.

In September, 1830, a youth of twenty-three came to Fayette, New York, where the Church had been organized five months before.

He was from Ohio, and was a preacher in the Campbellite Church. For some reason, unknown even to himself, he made a journey of several hundred miles, with his wife, to New York, where his father’s family lived. On his way there he stopped off to see some friends. Here he came across a strange book, called the Book of Mormon. He was told that this book had been revealed by an angel to Joseph Smith, and been translated by him from some gold plates.

This interested him very much, for he believed in angels and revelation, and had often wondered about the origin of the American Indians.

So he read the book eagerly. And, what is more, he believed it, and made up his mind to pay a visit to the young man who had been so highly favoured of God. Thereupon he sent his wife on to his folks and went himself to Fayette. Here he was baptized.

This youth was Parley P. Pratt, who afterwards became an apostle in the Church.

Not long after this Elder Pratt, with others, went on a mission to the frontiers in Missouri, to preach the new message to the Indians. He took with him copies of the Book of Mormon. One of these he left at the home of a man named Carter, who lived out some distance west of Kirtland, where the missionaries had converted more than a hundred people.

Carter read the Nephite Record, believed it, went to Kirtland, was there baptized and ordained an elder, and, returning to his home town, converted sixty persons.

Out of Boston lived a practising physician by the name of Willard Richards. This was in 1835.

He had heard that somewhere in the West a young man named Joseph Smith had found a gold Bible. But he had paid no attention whatever to the rumours about the Prophet and about the people who believed in him.

One day he visited his cousin, Lucius Parker. It happened that Brigham Young had left at the Parker home a copy of the Book of Mormon. Dr. Richards, on seeing the volume lying on the table, picked it up and began to read it. After reading half a page, he exclaimed:

Either God or the Devil has had a hand in the making of this book, for man never wrote it!

Twice over he read the book, and that within ten days. And he believed it to be true. Pretty soon, after arranging his affairs, he moved to New York State, joined the Church, and became an active worker in the new organization. At different times he was private secretary to the Prophet and counsellor to President Young.

That is what the Book of Mormon did for these three men. And what it did for them it has done for tens of thousands of others—men and women.

Aside from the Bible itself, no book has so greatly influenced the lives of people as the Book of Mormon.

Other books there are, of course, that have influenced human life. Some of them have created revolutions in the world of thought and action. Darwin’s Origin of Species has done that. But the influence of such books has not been directly, as a rule, through the reading of them by the masses, but rather indirectly through the speech and writings of men who have studied them, through the wide dissemination of the ideas they contained.

But the influence of the Book of Mormon has often been direct on the masses. Men and women have read it by the hundreds of thousands, and been remade by its powerful words and story. And this has been going on for a hundred years in all the civilized nations of the globe. It is written, not in the learned words of the scholar, but in the common vernacular of the people. In its pages are the things that the masses can understand, because they are the things and the ideas they themselves have experienced in one form or another.

A Scottish woman in the early days of the Church, a convert and the wife of a sea captain, once put in the bottom of her husband’s trunk a copy of the Book of Mormon as she packed it for him. He was not a member of the Church, and would never either talk about religion or read any of the literature concerning it, and he was very bitter over the fact that his wife had joined “Mormonism.” This placing of the Nephite Record in his way was the last daring resource of his tactful wife.

He came back from the ocean voyage on this occasion a convert to the faith, and was baptized as soon as he landed on his home shores. The Book of Mormon had done it. Things going wrong with him on the trip, he ransacked his trunk for something to read, and ran upon this book, the only piece of reading matter there. In sheer hunger for something to occupy his mind with, he read it through more than once—with the result stated.

There have been a great many cases like that, where people have been led into the Church in some humble way by the Book of Mormon, that no one has known of the means through which it was done.

But the influence of the Book of Mormon has been indirect, too, like that of other great world books. That is, people who have not read it have nevertheless been greatly affected by its contents.

They have been influenced by some of its dynamic sentences: “I know that the Lord giveth no commandment unto the children of men, save he shall prepare a way for them that they may accomplish the thing which he commandeth them.” That is from Nephi. And Lehi says, “Adam fell that men might be; and men are that they might have joy.” These, and many like them, have become so commonplace among our sayings that doubtless there are persons who do not really know their source.

And people have been influenced in their lives by some of the scenes in the Book of Mormon, although they may never have read these in the Record itself. That one where Lehi’s family wanders in the wilderness on their way to the Promised Land, because God has commanded them; the scene in which the converted Lamanites lay down their lives rather than take up their swords to shed human life; that one in which the faithful Teancum steals out at night to plunge a javalin into the heart of the enemy of his people and loses his own life in the act; the picture of the last days of Moroni, son of Mormon, as he snatches a few moments from his dangerous situation to set down the last words in the gold book his father has left him—those words that have been quoted a million times about how to test the truth of the Book of Mormon. These all, and others as vivid, have become indelible on minds that have never gone to the place where they are to be found in detail.

And the influence of the Book of Mormon has always been good. That is the final test of the worth of a book. Not whether it is well written, not whether this one or that one wrote it, not the question of time or place, but how does it affect the reader—this is to go to the heart of a bit of reading of any sort. Tens of thousands of men and women in modern times can testify that the Nephite Record, in the language of the book itself, has “led them to righteousness” in their lives. It has helped them to bear the burden in the heat of the day.

Among the indirect effects of the Book of Mormon not the least by any means is that which has come to the descendants of those about whom the Record tells—the American natives.

The Latter-day Saints have sympathized with the American Indian, because through the Book of Mormon they knew how he came to be what he is. And they have always sought to treat him with humanity and kindness.

The Book of Mormon has created this attitude.

The Nephite Record had no sooner been published in English than some Church members went to the borders of the United States to see what could be done to redeem the natives there through the record of their forefathers. This was known as the Mission to the Lamanites. It did not succeed in the way the missionaries hoped, but it exhibits the attitude of the early Church toward the descendants of Lehi and Mulek.

Later, when the saints came West, one of their problems grew out of their relations with the Indians. But it was the Book of Mormon ideas that solved this problem for the “Mormons.” Said Brigham Young, “It is better to feed than to fight the Indian.” His general policy with them was to seek to help them, rather than to antagonize them, to deal out justice rather than cruelty and deceit. And this policy was followed in the main. The result was that the “Mormon” people here had less trouble with the natives than did any other colonists in the nation.

Nothing better expresses the spirit of the saints in their relation to the Indians than the work of Jacob Hamblin, the “Mormon” Leatherstocking, as he was often called.

Shortly after he came to Utah he was sent at the head of some men from Tooele to capture a band of Indians that had stolen cattle belonging to the settlers there. On reaching the camp of the natives, he induced the leaders to go with him to Tooele, on the promise that their lives would not be endangered thereby. But when Hamblin got to the settlement with his prisoners, the leader of the colony ordered the natives to be lined up against the wall and shot to death. Hamblin protested, but to no avail.

In the end he sprang in front of the line of red men and said to the white leader:

Let me be the first one to be shot. I gave my word of honour to these people that they would be spared. If that word is not to be honoured, then I will die with them.

And he explains that, just before this, he had a very strong feeling that if he never harmed these barbarians, he would never be harmed by them. “I would not have hurt them,” he adds, “for all the cattle in Tooele Valley!”

During the rest of his life he devoted himself to the education of the Indians. He studied them, he ate with them, he conversed with them, he worked with them, and he prayed with them in their own simple way. Also he never deceived them. And to the end of his long life his name among the Indian tribes hereabouts was the synonym of integrity and fair dealing. He got into many close places daring his life, where his life was at stake, but his record always palled him through unscathed.

And the influence of the Book of Mormon will yet redeem the red man—not only the few hundred thousand in the United States, those on its reservations, but also the millions of other descendants of Book of Mormon peoples in Mexico and Son th America.

Probably those fine spirits who indited the pages of the smaller and the larger plates of Nephi, as well as the last of the Nephite historians, never dreamed that their work would have such a profound influence on whites and reds generations after they themselves were in their graves. Bnt such has been the fact. Thousands upon thousands of men and women in the last hundred years bless the names of those writers for having brought peace and hope into their hearts and goodness into their lives; and doubtless many millions yet to come will do the same.—(Published in The Relief Society Magazine, June, 1932.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.