Magazine

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (6 October 1910)

Title

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (6 October 1910)

Magazine

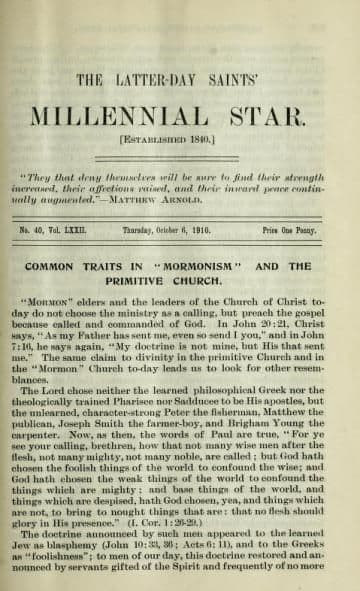

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1910

Authors

Brookbank, Thomas W. (Primary)

Pagination

628–631

Date Published

6 October 1910

Volume

72

Issue Number

40

Abstract

This series discusses the Babylonian and Israelite people who established Book of Mormon civilizations. Brookbank suggests that the Jaredites were Semites. The ancient ruins left in America have distinct Babylonian and Assyrian influence. The Nephite-Israelite people of the Book of Mormon have also left their mark upon civilization. The second part discusses enclosed courts, parallel halls, the lack of windows, sculptured pavements, and the lack of internal staircases.

PARENTAGE OF ANCIENT AMERICAN ART AND RELIGION.

(Continued from page 614.)

4. Enclosed Courts, and Simplicity in General Plan of Edifices.

The palace temples of Assyria were series of halls and chambers, and the structures that enclosed them in Sargon’s royal residence, for example, consisted of a series of buildings ranged around immense courts—there being a number of the latter.

An exact counterpart of this simple plan with its associated courts, is found in the ruined palaces of America, as anyone will perceive from an examination of the plan of the Palenque palace; and from a perusal of the text of Stephen’s works, and that of Baldwin. “A bewildering maze of courts and buildings” is a portion of the description given by the latter of some ruined structures at Mitla, and there is all the other evidence required to show that the Assyrians never did out-do the ancient Americans in ranging buildings around open courts. This architectural feature was equally characteristic of the structures built by both peoples respectively.

5. Parallel Halls.

The long, narrow room or hall style of apartments seems to have completely entranced the Assyrians, and so a spacious room at Nimroud, one hundred and sixty-two by sixty-two feet, was divided lengthwise by a wall twelve feet thick, making two halls of the original, and equal to each other in size (American Encyclopedia Britannica') or one hundred and sixty-two by twenty-five feet.

Not to be outdone in matters Assyrian, architecturally, the builders of the “Casa del Gobernador” at Uxmal, also divided a large apartment, sixty by twenty-seven feet, by a wall three and a half feet thick—the builders apparently observing about the proper proportions in the thickness of the dividing wall to that in the Assyrian pattern. No implication that the American builders ever saw the parallel halls at Nimroud is intended; but all the facts relating to this matter of parallel halls manifest quite plainly that the conceptions of the American architects were cast in an Assyrian mold, and case-hardened thoroughly, too, since the great palace at Palenque has two parallel halls, or corridors, running round all four of its sides. In front, these are about nine feet wide. The whole compass of the building is several hundred feet.

6. No Windows.

Speaking of the apartments in the Chaldean buildings, Ridpath says that it is not known by what means light was admitted to them; nor were the palaces of the Babylonians pierced for windows; and no known remains of them have been found among the Assyrian ruins. How a people who were so civilized as the Babylonians, and so far advanced in many of the useful and the fine arts, endured to live without natural light in the vast interior of their palaces, is a characteristic not easily accounted for, but they evidently did so live, unless they had some device, for admitting light, that is not known.

A similar lack of lighting facilities was also existent in the ancient American structures. An exception must be made in favor of the Peruvians, who erected some buildings that were provided with window apertures; but throughout all the other regions of America where once a highly civilized race of people dwelt, their finest edifices show that, like the Babylonians of old, they did not have windows. The light that entered through the doorways seems to have satisfied their desires and needs; but even with this inadequate lighting arrangement, we find that often, as if natural light were a burden to the ancient lords of America, an inside wall, with little intervening space between it and the outer one, was built up, thereby shutting out almost completely the light that did enter through the exterior doorways; and as in the example of a palace at Uxmal, a long outside wall was sometimes erected without any means of egress, or for the admission of light.

These remarks are made in view of the fact that a few apertures altogether have been found in walls of buildings not within the confines of Peru. This departure from general conditions is valued at its full worth. If those apertures were intended for windows— which is by no means certain—then it is manifest that all the civilized peoples of this land in early times understood a superior plan for admitting light to their dwellings; and their failure to avail themselves of its benefits wherever needed, shows how firm was the grip that Babylonian customs had upon them, for like their progenitors across the seas, they burrowed in the gloomy recesses of their palatial abodes without the natural light of day. The advanced stage of the civilization of both the Babylonians and the ancient Americans, while content, nevertheless, to live under the barbarous conditions just noticed, and in palaces at that, are inharmonious, but mutually shared mental characteristics, which serve to impress us strongly with the belief that all these peoples learned their arts in the same school, and were mentally dove-tailed to fit together as a family unit.

7. Sculptured Pavements.

No one should pass this specification by with a superficial notice: for the idea of sculpturing a pavement is eminently unique and distinctive. The description of the Assyrian example is found in the American Encyclopedia Britannica, and is as follows: “Of ornamental pavements there are admirable examples from Kouyunjik at the British Museum, and from Khorsabad at the Louvre, both covered with delicate carving in alabaster of nearly the same pattern. It is difficult to conceive how such delicate work could have been used in paving, and still retain its beautiful sharpness, for it was not filled in to protect the pattern.”

Turning our view to specimens of similar work in ancient America, we find an account of them given in the volumes just named. Speaking of a magnificent palace at Uxmal, it says that “the fiat roof of the building has been externally covered with a cement. In a building placed on a lower level is a rectangular court, which has been once wholly paved with well-carved figures of tortoises in demi-relief. These are arranged in groups of four, with their heads placed together; and from the dimensions of this court, this ‘Sala de las Tortugas’ must have required 43,660 of such carved stones for its pavement.”

Now, unless it can be shown that such work in pavements is not uncommon, or that it might be readily suggested originally to the architects of a people wholly unrelated, and unknown to each other, the carved Assyrian pavements and those at Uxmal in America must stand as manifest evidence that the ancient people of this country and the Assyrians are related by racial ties, or, at least, got their artistic ideas from the same source.

But such work is not common. On the contrary, it is extremely rare—perhaps never found outside of Babylonian regions and in America; nor is the conception of such work readily suggested to the mind, or specimens of carved pavements would be more widely discovered.

8. No Internal Staircases.

The American Encyclopedia Britannica states, that so far as it is aware, no internal staircases have been found in the ruined Assyrian buildings, and wanting there one could scarcely expect to find that the Babylonians or the Chaldeans made use of them. Stephens, describing a tall building at Palenque, observes that “there is no staircase, or other visible communication between the lower and upper parts of the building.” Respecting another of the tall buildings there he remarks that “as before, there was no staircase or other communication inside or out, nor were there the remains of any.” Remains, however, of staircases exist in two other buildings at Palenque; in one instance in the edifice which is distinguished as “Casa No. 4,” and the other is in the tower of the palace there. It is clear from these facts that the ancient Americans understood how to design buildings with internal staircases, but the Babylonian plan of getting along without them was too well fixed to be deviated from generally by the ancient architects of this land. The immense fiat roofs of some of their structures would have made admirable view-points, with the additional advantage of affording opportunities for out-door sleeping, in a hot climate, where plenty of fresh air could be enjoyed. But though they knew how to provide facilities, easy of access, for enjoying the pleasures and benefits mentioned, together with others, they could not or would not trangress against the customs of the old Babylonian homestead.

Such facts as these, with others already submitted, show common and peculiar mental characteristics, which, we think, can be attributed with little reason to peoples of no racial affinity; while on the other hand, they manifestly offer good ground for concluding that those who manifested these like traits in common, under the favorable conditions of a highly civilized life, were of one and the same family.

(To be continued.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.