Magazine

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (27 October 1910)

Title

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (27 October 1910)

Magazine

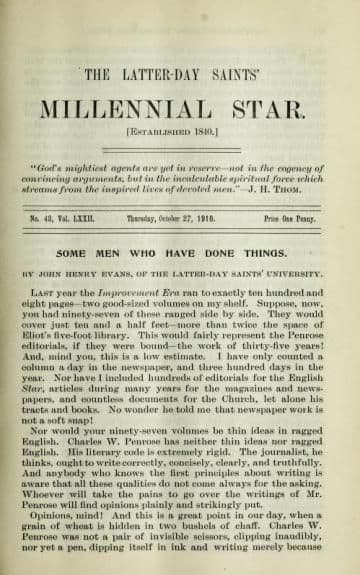

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1910

Authors

Brookbank, Thomas W. (Primary)

Pagination

684–686

Date Published

27 October 1910

Volume

72

Issue Number

43

Abstract

This series discusses the Babylonian and Israelite people who established Book of Mormon civilizations. Brookbank suggests that the Jaredites were Semites. The ancient ruins left in America have distinct Babylonian and Assyrian influence. The Nephite-Israelite people of the Book of Mormon have also left their mark upon civilization. The fifth part continues the discussion of adjunct structures, and pyramid temples.

PARENTAGE OF ANCIENT AMERICAN ART AND RELIGION.

(Continues from page 663.)

According to the plan given by the author named, and his general descriptive text, we find the following particulars in the Palenque (harem) buildings which correspond perfectly with the Assyrian pattern.

(1.) A great tower is behind the harem.

(2.) The harem is shut off completely from communication with the outer world, and the inmates were practically in prison.

(3.) The long narrow hall for banqueting purposes is there.

(4.) A number of rooms for habitation are marked on the plan.

(5.) The vestibule (at the southern entrance to the palace), is provided for.

(6.) The vestibule has two means of egress.

(7.) One of these door-ways leads to the apartments of the harem.

(8.) The other opens on a hall or passage which affords communication with the court of the tower, and all the rooms and offices of the principal building.

(9.) The plan of the whole structure afforded the king access to his harem without being seen by the public.

(10.) A variation in construction which serves to confirm the common original of the plan of these harems, rather than to manifest any essential dissimilarity, is that while the door of egress from the vestibule to the interior of the harem opened on “a long narrow court in the Assyrian building, in the American the corresponding door opened on “a long, narrow hall.”

Other noticeable common features are: (11.) No windows. (12.) No stairways. (13.) A terraced foundation. (14.) The harem is an independent building. (15.) The approaches are by broad flights of steps. (16.) A large court adjoins the harem. Additional similar characteristics might be mentioned; but these suffice for present purposes.

The Assyrian structure contained more rooms, halls and courts than the American duplication; but the greater size of the former afforded facilities for them. However, neither the size of the building, nor the number of halls, rooms and courts are material to affect the identity of the general plan.

McCabe's description of Sargon's royal harem can be applied to the one at Palenque with the variation of a few words only.

These sixteen points of identity or similarity combined in one structure, or connected with it, supply unimpeachable evidence that the Assyrians and the ancient Americans were mentally a unit, were dispositioned alike, and founded their architectural plans on the same original.

According to what is called the law of “chance,” there is only one in millions, that the Palenque (harem), with its associated features, could have been built so completely in conformity with the Assyrian model, if there had not been a known common original upon which they were both based. If we had no other data than what has just been submitted, upon which to rest this case, the proposition that the people of Mesopotamian regions and the ancient Americans were of one and the same family, or certainly got their architectural designs from the same source, could not be controverted successfully.

23. Pyramidal Temples.

In Chaldea, as early as the era of Nimrod, the temples were usually pyramidal in form, and were built in successive steps or stages to a considerable height; and were placed so as to face the cardinal points of the compass.

This form was still prevalent in the reign of Shalmanezer, or about B.C. 1320. It is therefore apparent that for more than a thousand years the idolatrous Semites of the Babylonian regions had not materially altered the design of their temples. This unique plan for them being a clearly favorite one with the peoples of the Tigris and Euphrates districts, was bound to manifest itself to a greater or less extent in other lands permanently settled by them.

If this temple design was not executed, because of special modifying circumstances by every branch of the Semitic family, yet we find it so manifestly the same wherever observed that we know from whence the plan was derived. The Japhethites and the Hamites do not seem to have been greatly impressed in favor of the pyramidal temple design, and a line of distinction can thus be drawn between some of the Semites and the other peoples just named.

An authoritative description of pyramidal temples in the Old World reads as follows: In Chaldea “the grandest of all these and the most interesting is the Birs Nimroud, near Babylon. * * * Another example is at Mugeyer, which was one hundred and ninety-eight feet by one hundred and thirty-three at the base and is even now seventy-feet high, and it is clear that both it and the Birs were built with diminishing stages, presenting a series of grand platforms, decreasing in length as they ascended and leaving a comparatively small one at the top for the temple cell.”

(To be continued.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.