Magazine

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (24 November 1910)

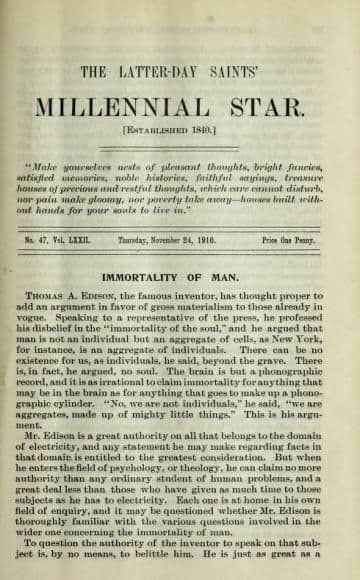

Title

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (24 November 1910)

Magazine

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1910

Authors

Brookbank, Thomas W. (Primary)

Pagination

740–743, 747

Date Published

24 November 1910

Volume

72

Issue Number

47

Abstract

This series discusses the Babylonian and Israelite people who established Book of Mormon civilizations. Brookbank suggests that the Jaredites were Semites. The ancient ruins left in America have distinct Babylonian and Assyrian influence. The Nephite-Israelite people of the Book of Mormon have also left their mark upon civilization. The ninth and final part discusses an altar found at Copan and headdresses associated with the Aaronic priesthood.

PARENTAGE OF ANCIENT AMERICAN ART AND RELIGION.

(Continued from page 733.)

Mr. Baldwin might have added, we think, that very probably both the ancient Americans and the Phoenicians borrowed their notion of sacred serpents from the Israelites, who apparently practiced serpent adoration from the very beginning of their national existence.

Sun worship and serpent figures, either worshipped or used as religious symbols, were associated together in Phoenicia, Palestine and ancient America; and for this reason both of these idolatrous features of a common system have been considered together under this one number.

40. A Copan Altar. A Revelation of Priestly Judaism.

In Stephen’s Travels in Central America, etc., Vol. 1, facing page 141, and following 142, there are representations of the top and the four sides of a remarkable altar which is found among the ancient American ruins at Copan. The sides altogether contain sixteen sculptured human figures, and the top is divided into thirty-six sections of hieroglyphics. Among the latter are symbols which readily suggest the two stone tables on which were originally written, by the finger of God Himself, the ten commandments. They are apparently inscribed with hieroglyphics to indicate doubtless that they are intended to represent records of some kind. Placed crosswise on one of the tablets is evidently the symbol of a sealed book, or roll of writing, resembling the ancient style of books. The base of the tablet which has the sealed roll upon it, rests upon a symbol which to us represents nothing else so well as the several phases of the moon in their progress from a small disk to a full orb. There are also two crosses. These are symbols which, as we all know, could be very appropriately used to represent matters of one kind or another connected with the Mosaic or the Christian dispensations.

But it is when we come to an examination of the figures that are carved on the sides of the altar, that we find portrayed evident representations of Jewish practices, priestly costumes and symbols; and to these our attention is now directed by an enumeration, as follows:

(1.) The two principal figures are seated in the oriental fashion. Not much importance is attached to this circumstance, yet it shows that this custom of the East was known in the West, and its practice here is in harmony with the Book of Mormon claims.

(2.) The figures are all bare-footed. It is of no avail to our opponents to claim that this was a general custom with the priestly orders of a number of Asiatic nations; for that fact does not explain how it came to be a priestly observance in America anciently. Doubtless the practice of ministering bare-footed in holy places was confirmed—not instituted—among the Israelites when the Almighty, on a certain occasion, commanded Moses to take off his shoes because the ground upon which he stood was holy. (Ex. 3:5.) Joshua at one time was also commanded to loose his shoes from his feet for a like reason. (Josh. 5:15.) In both of these cases the command to stand bare-footed is manifestly given not to institute a practice, but to call the attention of Moses and Joshua, respectively, to the fact that the ground on which they then were was holy, though it was not within any known sacred enclosure, or was not a part of a visible holy place. In neither instance can we justly infer that the observance of this custom was then first ordained, and how much farther back in the history of the Israelites one would have to go in order to find the beginning of the practice, is, perhaps, now merely conjectural. It was at all events a very ancient custom among the priestly orders of that people.

(3.) Three figures of serpents are carved on the sides of the altar in association with those of the priests. Attention having already been called to the position that the brazen serpent occupied in both sacred and idolatrous Israelitish affairs, no further remarks respecting the serpent representations on the altar at Copan are necessary.

(4.) The Figures of the priests are all provided with breast-plates and,

(5.) The breast-plates are all inscribed, as Stephen’s illustrations indicate.

These two points in order to avoid repetitions will be considered together. From the Biblical records we learn that whenever Aaron went into the holy place, he was required, by the command of God, to wear a “breast-plate of judgment,” and upon it was written the names of the twelve tribes of Israel. Concerning the use of such breast-plates among the ancients, Dr. Adam Clarke, in his comments on Exodus 28:30, after making some remarks respecting those provided for the Israelitish priests, and referring to similar badges of authority in use among the Egyptians and the Chinese, says, “All these seem to be derived from the same source; both among the Hebrews, the Egyptians and the Chinese. And it is certainly not impossible that the two latter might have borrowed the notion and use of the breast-plate judgment from the Hebrews, as it was in use among them long before we have any account of its use either among the Egyptians or the Chinese.” The different mandarins still wear a symbol of this kind.

All these different badges were inscribed, or had upon them some token or insignia of office and authority. Now, those inscribed breast-plates, forming a portion of the vestments of the ancient American priestly orders, and practically identical in design, so far as one can determine from descriptions and illustrations, with those of the Aaronic priesthood under the Mosaic dispensation, almost compel the conclusion that the early people of this continent copied their ideas of the design and use of their breast-plates from the Israelites of Palestine, who in turn got all these matters from God.

But this case has yet another feature. If what has already been observed about these breast-plates show almost to a certainty a Jewish origin for them, to what conclusion shall we come as to the source from which those in America were derived, when we recall the fact that the breast-plate of judgment was a vestment of the Aaronic priesthood whose duty it was to attend to the public sacrificial ceremonials under the Mosaical law; and then turning our gaze to America, find that the breast-plates worn by the figures sculptured on the altar at Copan, are also identified with the altars of public sacrifice. The Aaronic priesthood, with its emblem of authority and sphere of service, are faithfully represented on that remarkable altar at Copan.

If there were any sort of confusion apparent in these matters, the evidence in favor of this conclusion would not be so convincing. If, for instance, the breast-plates were found on female figures, or only on those of kings and soldiers, and were associated with any department of governmental or religious service except that of the public sacrifices, there would be some grounds for claiming that chance conceptions in the ancient American mind could account for the similarity in design of those breast-plates. But the consistency everywhere apparent, as the case stands, can not with any show of reason be attributed to chance.

(6.) Aaronic Priesthood Head-dresses.

There yet remains for consideration a striking similarity between the headdresses on those carved priestly figures, and those which were appointed for Aaron and his sons when ministering in their holy office.

The Bible does not enter largely into a description of these coverings for the head, merely saying that there should be made for these officials “mitres of fine linen, and goodly bonnets of fine linen.” It appears from this language that the head-dress was to consist of two pieces. Dr. Clarke, in his notes on Exodus 28: 4, says that as the original word for “mitre” comes from a root that means to roll or wrap round, “it evidently means that covering for the head so universal in eastern countries which we call turban or turband. * * * The turban consists generally of two parts; the cap which goes on the head, and the long sash of muslin, linen, or silk that is wrapped around the head. These sashes are generally several yards in length. Josephus confirms this view, saying that the head-dress of the priests was made of thick swathes, doubled round many times and sewed together. (Antiq. chapter 7.)

Now, it is only necessary to take one brief look at the headdresses on the figures on the Copan altar to perceive that they are intended to represent “mitres or goodly bonnets” constructed by wrapping material of some kind round and round an inside body or cap.

Here, now, in another specification, we find a part of the habiliments of the Aaronic priesthood, as Divinely instituted among the Israelites in Palestine, represented as an essential of the dress of the priestly officials in Ancient America—shall we not say of the Aaronic priesthood in this country more than a thousand years ago; for its insignia occurs precisely where it should to sustain this view of the matter. Such appears to be a consistent interpretation of a number of interesting symbols that are carved in stone on the sides of that Divinely preserved altar of testimony at Copan. Whether this altar is the one, or is not the one, to which reference is made in Isaiah 19:19, we leave each of our readers to surmise for himself. Doubtless when the hieroglyphics carved on its top are deciphered we shall have additional data upon which to base a conclusion.

These enumerated similarities, forty in all, but covering more than half a hundred different specifications, supply the volume of evidence to be submitted at present in substantiation of the second and the third propositions which were stated in the first portion of these remarks—some of the points considered applying to one of them, some to the other. If combined they do not clearly manifest that the ancient peoples of America were derived from the very sources claimed for them by the Book of Mormon, we make bold to say that no people anywhere ever erected architectural or sacred monuments in distant lands colonized by them, that were of the least value in tracing racial descent. The signs, tokens, monuments, etc., examined in this case range from recesses in walls for door-hinges to windows and stair-cases; from long, narrow halls and rooms to prison-like harems; from simple building plans to mazes of courts and surrounding structures; from terraced foundations to terraced superstructures; from inscribed walls to ornamental slabs set in them; from bas-relief work to superb mosaics in relief; from ancient American hieroglyphical symbols to similar ones in form and signification occurring in Egypt and the East; from idols and altars at the base of temples to the temple cells or shrines at the summit; from bare-footed priests to serpent worship; from soldier’s trousers to the Divinely ordained vestments of the Aaronic priesthood; and everywhere we find easily read signs of the occupancy of this land in ancient times by both Babylonians and Israelites. The voices that rise from the ruins of olden times in this land of America, unite in proclaiming the divine origin of the Book of Mormon.

In the course of these remarks we have found so many noteworthy features of similarity between the arts, etc., of Chaldea, Babylonia, and Assyria on the one hand, and those of ancient America on the other, that it is scarcely conceivable all of them could have been developed so nearly alike, in countries so far apart, unless there was frequent communication between them during long periods of time after this land was first colonized from Babylonia. Such communication was not improbable, since, as already observed, a route either east or west from the Babylonian regions was known in early times; and moreover, the Phoenicians who visited America in ancient days (See Baldwin's Ancient America, pages 172-3), may have been “Captains of Industry” who had regular lines of travel and traffic established across the Atlantic, which doubtless was not so broad along some routes of passage, nor so dangerous as it now is; before the lost “Atlantis” was buried beneath its waves.

Snowflake, Arizona. Thomas W. Brookbank.

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.