Magazine

Evidences of the Book of Mormon—Some External Proofs of Its Divinity: Part I. The Book

Title

Evidences of the Book of Mormon—Some External Proofs of Its Divinity: Part I. The Book

Magazine

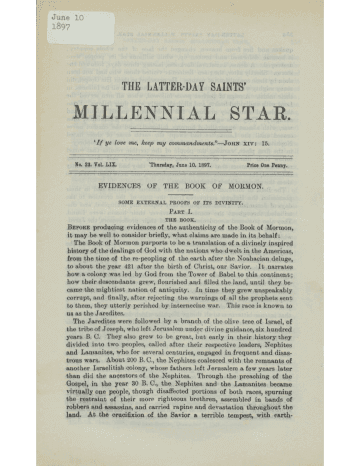

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1897

Authors

Reynolds, George (Primary)

Pagination

353–358

Date Published

10 June 1897

Volume

59

Issue Number

23

Abstract

This is a five-part series that includes a brief overview of the Book of Mormon, an account of Spanish conquerors who destroyed evidence of Hebrew influence reasoning that “Satan had counterfeited in this people the history, manners, customs, traditions, and expectations of the Hebrews,” a description of artifacts containing Hebrew characters, and evidence that the religious traditions of the Indians corroborate Book of Mormon statements. The first part covers the Book of Mormon itself.

EVIDENCES OF THE BOOK OF MOBMON.

SOME EXTERNAL PROOFS OF ITS DIVINITY.

PART I.

THE BOOK.

Before producing evidences of the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, it may be well to consider briefly, what claims are made in its behalf:

The Book of Mormon purports to be a translation of a divinely inspired history of the dealings of God with the nations who dwelt in the Americas, from the time of the re-peopling of the earth after the Noahacian deluge, to about the year 421 after the birth of Christ, our Savior. It narrates how a colony was led by God from the Tower of Babel to this continent; how their descendants grew, flourished and tilled the land, until they became the mightiest nation of antiquity. In time they grew unspeakably corrupt, and finally, after rejecting the warnings of all the prophets sent to them, they utterly perished by internecine war. This race is known to us as the Jaredites.

The Jaredites were followed by a branch of the olive tree of Israel, of the tribe of Joseph, who left Jerusalem under divine guidance, six hundred years B.C. They also grew to be great, but early in their history they divided into two peoples, called after their respective leaders, Nephites and Lamanites, who for several centuries, engaged in frequent and disastrous wars. About 200 B.C., the Nephites coalesced with the remnants of another Israelitish colony, whose fathers left Jerusalem a few years later than did the ancestors of the Nephites. Through the preaching of the Gospel, in the year 30 B.C., the Nephites and the Lamanites became virtually one people, though disaffected portions of both races, spurning the restraint of their more righteous brethren, assembled in bands of robbers and assassins, and carried rapine and devastation throughout the land. At the crucifixion of the Savior a terrible tempest, with earthquakes and fire from heaven, changed the face of the whole country; it became deformed and broken up, while millions of its people were destroyed. A dense, unnatural darkness, lasting three days, followed the storm. Shortly after, the risen Redeemer visited those who had not been slain by these convulsions of nature. He preached to them His Gospel, did many mighty works, and established His holy Church in all its fullness, in their midst. A reign of perfect peace followed, when all men served the Lord with undivided hearts, and all dealt justly with their fellows. From this blessed state they gradually fell to depths of untold iniquity and savagery. They once again divided into Nephites and Lamanit.es; then war, with almost unparalleled horrors, followed; and the conflict never ceased until the Lamanites had swept the earth clear of their hated Nephite foes. But, running through all the book is a vein of prophecy— in the first place, warning the people of the terrible results that would follow their disregard of God’s long-suffering mercy, and then giving repeated assurances that at a later time, after they had been sufficiently chastened, He would hold them in remembrance, and more than restore to them the glories of their brightest days.

The Book of Mormon tells us that the ancient Nephites had in their possession the Hebrew scriptures from the time of the creation to the days of Jeremiah. These scriptures they copied and multiplied, and distributed throughout the continent wherever their homes were found. They also possessed a condensed history of their predecessors, the Jaredites, and themselves kept many records, ecclesiastical and secular, on which the annals of the race were engraved. These records were a source of great annoyance to the Lamanites, who, when they annihilated the Nephites, sought, in their furious hatred, to obliterate the remembrance of their existence by destroying their records also. Everything that reminded them of their former foes was consumed, and then they fell to fighting among themselves. Out of these contending factions tribes arose who, as time wore on, laid the foundations of the varied civilizations that held sway on these continents between the days of the destruction of the Nephites and the time of the coming of the Spaniards. The succeeding years also brought a change of heart; following generations did not feel that intense bitterness to all things Nephite which dominated the breasts of those who were actually engaged in the last deadly struggle with their brother’s house, and after awhile they began to feel a curiosity to learn the history of their forefathers. They were well acquainted by tradition with the fact that the Nephites had kept many records; they also knew that these books had been destroyed whenever found; still there were some copies, or fragments of copies that had been hidden when the spirit of destruction raged with the greatest intensity. These remnants were gathered and copied and their contents accepted as true, at least, by some of the tribes. Boturini1 tells us, that in one tribe of the Lamanites, afterwards known as the Toltecs, about the year of our Lord 660, Huimattzin, a celebrated astronomer, “called together all the wise men, with the approval of the monarch, and painted that great book which they called teoamoxtli,2 that is, divine book, in which with distinct figures account was given of the origin of the Indians; of the time of the separation of the people at the confusion of languages; of their peregrinations in Asia; of their first cities and towns that they had in America; of the foundation of the empire of Tula, of their progress until that time; of their monarchs, laws and customs; of the system of ancient calendars: of the character of their years; and symbols of their days and months; of the signs and planets, cycles and series; of the first day of new moon; of the transformations, in which is included moral philosophy; as also the arcanum of the vulgar wisdom hidden in the hieroglyphics of their gods with all that pertains to religion, rites and ceremonies.”

What was done in this instance was probably repeated in many others, so much so that when Cortez3 and his associates overcame the Mexicans they found the country full of these historical records, which were mostly in the shape of picture maps. These records when translated were full of evidence that the Mexicans were a remnant of the house of Israel. But the Spanish Catholics in their blind fanaticism, would not admit this truth; they fancied that the prophecies regarding the scattering of Israel were all fulfilled in the dispersion of the Jews; as a result the American Indians could not be of the chosen race; to believe so would be contrary to God’s word, and consequently was heresy. Therefore a policy was adopted by the Spanish Roman Catholic authorities to hide and distort the truth. All the ancient writings that could be found were destroyed; cruel and inhuman penalties, such as burning to death, were inflicted upon those natives in whose possession any of these ancient records were discovered; the writings of those prelates and others who favored the idea of the Israelitish ancestry of the natives were taken to Spain, destroyed, scattered or hidden away, and to this day by far the greater portion, from one pretext or another, has never been published. It may be well to observe that the Spanish historians “were all members of the Romish Communion, the greater part ecclesiastics, and, as their names indicate, chiefly of Hebrew descent.

“Those early Spanish writers unanimously recognized and acknowledged the manifold analogies which demonstrate the transference of the Levitical economy to the New Continent; but while some of them discerned in this circumstance an indisputable proof of the Hebrew origin of the newly- discovered people, others accounted for this almost fac simile resemblance by asserting that Satan had counterfeited, in this people (whom he had chosen for himself), the history, manners, customs, traditions, and expectations of the Hebrews, in order that their minds might thus be rendered inaccessible to the faith which he foresaw the Church would, in due time, introduce among them.

“The historians who ranked themselves as the advocates of the former of these alternatives, were Las Casas,4 Sahagun,5 Boturini, Garcia,6 Gumilla, Benaventa, and Martyr. Those who maintained the latter hypothesis were Torquemada,7 Herrara,8 Gomara,9 D’Acosta,10 Cortez, D’Olmes, Diaz.11 The circumstances in which Herrara and Gomara were placed, (the former having been royal historiographer, and the latter chaplain to Cortez), admitted of their taking only the orthodox view of the subject. The ‘secret correspondence’ of Cortez with Charles V., together with the rigorous censorship which was exercised by ‘the holy tribunal,’ sufficiently prove that even this least offensive view of the subject was to be expressed with reserve.”12

Much as we may deplore the fanaticism and folly that cause the destruction of such vast quantities of priceless records, yet we believe we can trace the hand of the Lord therein. Had all those writings been preserved, when the Book of Mormon came forth, the world would have immediately rejected it. Men would have declared that it was simply a paraphrase made by Joseph Smith, of the ancient Mexican and Peruvian records in the language and style of the English Bible, intermixed with portions of the Old and New Testaments, to pad it out and make a good-sized book of it; and there would have been far more difficulty in getting them to examine its claims as a portion of holy scripture, than there is even now. A very faint idea of what could have been published, had the Spaniards not prevented, may be surmised, when, from the few fragments that have been permitted to come to light, one author writes concerning the American aborigines: “They assert that a book was once in possession of their ancestors, and along with this recognition they have traditions that the Great Spirit used to foretell to their fathers future events; that he controlled nature in their favor; that angels once talked with them; that all the Indian tribes descended from one man, who had twelve sons; that this man was a notable and renowned prince, having great dominions; and that the Indians, his posterity, will yet recover the same dominion and influence. They believe, by tradition, that the spirit of prophecy and miraculous interposition, once enjoyed by their ancestors, will yet be restored to them, and that they will recover the book, all of which has been so long lost.”13

Could anyone who has read the Book of Mormon give a better description of its contents than this extract does? Yet the book from which it is taken was published in London, before a Mormon Elder ever trod the ground of Great Britain, or any copies of Mormon’s record had been carried to its shores. Little did the author think, when he recorded these traditions, that the prophecy of the recovery of the book was already an accomplished fact.

The original of this ancient history was engraven on plates of metal, which were held together by three rings which ran through all of them, and in this way bound them together in the shape of a book. Some objection has been made by ignorant critics, to this statement, they affirming that the ancients did not use metal plates on which to engrave their records. In this they mistake. One writer (C.W. Wandell) says:

“There can be no well-founded objection to the Nephite record, from the material on which it is engraved; for the gold plate worn on Aaron’s head, on which was written ‘Holiness to the Lord,’ proves that the idea was known to them. Bishop Watson says: ‘The Hebrews went so far as to write their sacred books in gold, as we may learn from Josephus compared with Pliny.’ Watson’s Bib. and Theo. Dic. Art. Writing.

“Nor is the modern, book-like form of the volume any argument against its antiquity; for Bishop Watson in the same place says: ‘Those books which were inscribed on tablets of wood, lead, brass or ivory were connected together by rings at the back, through which a rod was passed to carry them.’”

Geo. Reynolds.

[To be continued.]

- 1. Boturini, Benaduci Lorenzo, a noted antiquarian. Born at Milan about 1680: died at Madrid, 1740. During eight years he traveled and lived among the Indians of Mexico, and collected several hundred specimens of their hieroglyphic records. He was despoiled of most of his collection and the greater part was permitted to perish through neglect. Some little of the results of his researches have been published.

- 2. One writer asserts that the exact meaning of the word Teoamoxtli is “The Divine Book of Moses.” If this be true, then the "Divine Book” was probably a reproduction of portions of the brass plates brought by Lehi and his colony from the city of Jerusalem.

- 3. Cortez, Hernando (sometimes called Fernando), the conqueror of Mexico. Born at Medallin, Spain, 1485: died near Seville, December 2, 1547.

- 4. Las Casas, Bartoleme de, a Spanish Dominican, celebrated as a defender of the Indiana, against their Spanish oppressors. He was born at Seville, 1474; died at Madrid, 1566. He came to America in 1502; returned to Spain in 1515, to intercede for the Indians, with King Ferdinand; he returned to Spanish America, in 1516, and twice afterwards returned to Spain, in his efforts to obtain justice for the natives. From 1544 to 1547, he was bishop of Chiapa, in Mexico. His history of the Indians was not published until 1875, but was well known before, through manuscript copies.

- 5. Sahagun, Bernadino de; born in Spain, about 1499: died in 1590. He was a Franciscan missionary and historian. From 1529, he lived in Mexico, where he held various offices. His historical works, published in modern times, were freely used in manuscript by the old historians.

- 6. Garcia, Gregorio. Born in Cozar about 1560; died in Beaza in 1627. He was a Spanish Dominican author. He traveled for twelve years in Spanish America, part of the time as a missionary among the Indians. A portion of his historical works have never yet been published and are probably lost.

- 7. Torquemada, Juan de. Born at Valladolid, Spain, about1545; died in Mexico, after 1617. A Spanish historian. He went to Mexico in his youth; joined the Franciscan order there, and was a professor in the college of Tlatelolco. His historical works are amongst the best of the early histories of Mexico.

- 8. Herrara, Antonio. Born at Cuellar, 1549; died at Madrid, 1625. A Spanish historian. Phillipp II. made him chief chronicler of America. Herrara published many historical works, the most important being those that related to America.

- 9. Gomara, Francisco Lopez. A Spanish historian, born at Seville, 1510; died after 1559. He was a priest and the chaplain of Cortez, but it does not appear that he was ever in America. Amongst his other works, he wrote one concerning the conquest of Mexico.

- 10. Acosta, Jose d’. A Spanish Jesuit historian and archaeologist; he was born in Old Castille, 1540; died at Salamanca, 1600. He went to Peru in 1571. He wrote a work entitled, “Natural and Moral History of the Indians,” which has been translated into many languages. He was appointed to many important positions after his return to Spain, in 1587.

- 11. Diaz, Del Castillo, Bernal. A Spanish soldier and author, who served under Cortez, in the conquest of Mexico. He was born about 1498; died in Nicaragua, about 1593. His history of the conquest of New Spain, though rough in its literary style, has remained a standard historical authority on the conquest of Mexico.

- 12. “The Ten Tribes of Israel,” Simon, London, 1836.

- 13. From a work on the origin of the American Indians, by C. Colton, London, 1833.

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.