Magazine

The Book of Mormon Confirmed (3 February 1898)

Title

The Book of Mormon Confirmed (3 February 1898)

Magazine

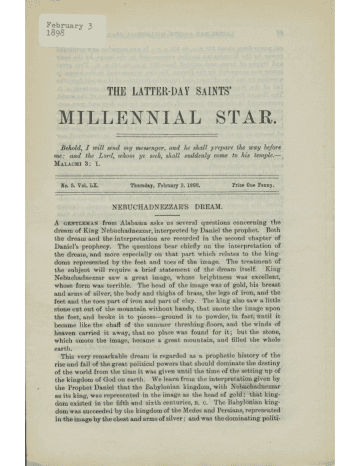

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1898

Editors

Wells, Rulon S. (Secondary)

Pagination

72–77

Date Published

3 February 1898

Volume

60

Issue Number

5

Abstract

This five-part series gives various external evidences of the Book of Mormon, including the archaeological findings that “point to successive periods of occupation” in ancient America, evidence of Hebrew origin/descent for the American Indians, and the idea that there was an advanced civilization in ancient America. It also discusses metal plates and provides geological proof of the great destruction recorded in 3 Nephi 8. The fourth part covers the evidence of advanced civilization in the Americas.

THE BOOK OF MORMON CONFIRMED.

[Continued from page 63.]

The Book of Mormon states that both the descendants of the colonists from the Tower of Babel and those from Jerusalem attained to a high degree of civilization, were acquainted with many arts; and also that they became very wicked, and destroyed each other in fiercely-fought battles. (See Mormon, chapter 6; also Ether, 15:2). The record gives the information that the first nation cultivated all kinds of fruit and grain; that they manufactured silk and fine linen, and possessed gold, silver and other precious things; that they had domestic animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats, swine, horses, elephants and others. (See Book of Ether, 9:17, 18, 19). The second nation found these same animals in the country (see I Nephi 18:25). It is also recorded that the latter people built cities (Alma 21:2) and temples (II Nephi 5:16); that they had coins of gold and silver (Alma 9:4–19), and used these and other metals in the arts, (Jarom 1:8); and that many records were kept by the people, (Helaman 3:13).

The evidences that the ancient peoples of America were highly civilized are numerous and undisputable. Only a very few of the many descriptions of ancient ruins discovered in various parts of America are given in the following extracts:

EVIDENCES OF ADVANCED CIVILIZATION.

“Much has been done in recent years to throw light upon the history of the ancient races of the east, but comparatively little interest has been taken, even by American archaeologists and scientists, in the ancient and marvelous civilization whose traces are to be found scattered over our continent, particularly in Central America and Mexico. That a civilization once flourished in these regions, much higher than any the Spanish conquerors found upon their arrival, there can be no doubt. By far the most important work that has been done among the remains of the old Maya civilization has been carried on by the Peabody Museum of Harvard College, through a series of expeditions it has sent to the buried city now called Copan, in Spanish Honduras. In a beautiful valley near the borderland of Guatemala, surrounded by steep mountains and watered by a winding river, the hoary city lies wrapped in the sleep of ages. The ruins at Copan, although in a more advanced state of destruction than those of the Maya cities of Yucatan, have a general similarity to the latter in the design of the buildings and in the sculptures, while the characters in the inscriptions are essentially the same. It would seem, therefore, that Copan was a city of the Mayas; but if so it must have been one of their most ancient settlements, fallen into decay long before the cities in Yucatan reached their prime. The Maya civilization was totally distinct from the Aztec or Mexican; it was an older and also a much higher civilization.

So far the Peabody expeditions have confined their attention to the temples and palaces, and though for several seasons quite a little army of natives has been engaged in excavating, yet the work that has been accomplished amounts to little in comparison with that which remains to be done. To clear the main structure alone will be the work of years. Could the vast structures be restored, our greatest buildings would seem as pygmies in comparison; and certainly no city of the modern world could boast such a profuseness and richness of carved and sculptured ornamentations. A stairway recently discovered is thirty feet in width, and ascends to the top of a pyramid one hundred and thirty feet in height. Each step is carved along the entire face with a row of hieroglyphs. A grand parapet, elaborately decorated with sculptures, ran up and down on either side while at different heights in the centre of the steps statues of men in gorgeous attire were seated one above the other. It is Professor Putnam’s intention to preserve every step and every piece of sculpture of this stairway, either in original or in cast, and to reproduce the whole structure at the Peabody Museum. Surrounded by ranges of steps or seats which inclose it on all sides but the southern, is what is known as the great plaza of Copan. This has the appearance of an amphitheatre, and within it are thirteen monolithic monuments elaborately carved, each having in front of it a sculptured block of stone, evidently an altar. Six of the monuments are standing in upright positions, but the rest are fallen idols. The dauntless six have maintained their positions for centuries, for they are accurately described by Palacio (in a letter sent to the king of Spain in 1576). The monuments average about twelve feet in height and three in breadth and thickness, and are cut from trachyte rock. On the front of each, and sometimes on both front and back are elaborately decorated human figures, while all sorts of grotesque representations of men and animals and masks and feather work chase each other and are intricately interlaced upon the monuments. The backs of these, and also sometimes the sides, are covered with hieroglyphs. Until they are deciphered it cannot be determined whether the human figures are intended to represent deities or heroes or are portraits of rulers or priests. In some instances vaults have been found beneath the monuments; they are constructed of squared stones laid without mortar, and are strong and well made.

So far all the buildings that have been explored are of the nature of palaces and temples. The chambers that have so far been cleared have been so bare of household goods as to suggest a voluntary abandonment of the city by its inhabitants. The only vessels found in the temples were huge stone urns decorated with grotesque figures and elaborate symbolisms. It has been suggested by some that these may have been incense-burners. The interiors of the walls were covered with a coat of plaster and decorated with stucco ornaments. Images, faces resembling portraits, and a variety of curious ornamentations of beautiful workmanship have been found where they had fallen from the interior wall. The stucco and the plaster covering the walls were decorated with various colors. The exteriors of the buildings were elaborately ornamented with statuary, figures of men and of animals.—Henry C. Walsh, in Harper’s Weekly, October, 1897.

“This edifice being solid in the interior for the whole space contained within 5,376,000 feet circumference, which it has to the before-mentioned height of 150 feet, is solid and levelled; and upon it there is another wail of 300,000 feet in circumference in this form, 600 feet in length, and 500 in breadth, with the same elevation (150 feet) of the lower wall, and, like it, solid and levelled to the summit. In this elevation, and also in that of the lower wall, are a great many habitations or rooms of the same hewn stone, 18 feet long and 15 wide; and in these rooms, as well as between the dividing walls of the great wall, are found neatly-constructed niches, a yard broad or deep, in which are found bones of the ancient dead, some naked and some in cotton shrouds or blankets of a firm texture, though coarse, and all worked with borders of different colors. … We know of nothing in Egypt or Persia to equal it. From the description, it must have been a vast tomb; but whether erected by the Indians before the Spanish discovery, or by remoter generations, cannot be decided. Yet the Judge says that the ingenious and highly-wrought specimens of workmanship, the elegance of the cutting of some of the hardest stone, the elegant articles of gold and silver, and the curiously-wrought stones found in the mounds, all satisfy him that that territory was occupied by an enlightened nation, which declined in the same manner as others more modern, as Babylon, Balbec, and the cities of Syria; and this, he says, is evidently the work of people from the old world, as the Indians have no instruments of iron to work with.”—Extract from a correspondent’s letter on a ruined building found by Judge Neito, at Cenlap, in the province of Chichapoyas, from the National Intelligencer.

“On the left bank of the river Montagna, in the lands called Quirigua, about six leagues from the town of Yzabal, on the Gulf of Dulce, there are some remains of antiquity, that, were they better known, would excite the admiration of archaeologists. They consist of seven quadrilateral columns, from 12 to 25 feet high, and three to five feet at the bases, as they now stand; four pieces of an irregularly oval figure, 12 feet by 10 or 11 feet, not unlike sarcophagi; and two other pieces, large square slabs, seven-and-a-half feet by three feet, and more than three feet thick. All are of stone resembling the primitive sandstone, and except the slabs, are covered on all sides with sculptured devices, among which are many heads of men and women, animals, foliage, and fanciful figures, all elaborately wrought in a style of art and good finish that cause surprise on inspecting them closely. The columns appear to be of one piece, having each side entirely covered with the figures in relief. The whole have sustained so little injury from time or atmospheric corrosion, that, when cleared from an incrustation of dirt and moss, they show the lines perfect and well- defined. Evidently they are the performances of a skillful and ingenious people, whose history has been lost probably for ages, or rather centuries. … Investigation as to their origin and purpose would lead into a labyrinth of conjecture. They suggest the idea of having been designed for historical records rather than mere ornament; and as so little is known of this country previous to the subjection of it by Pedro Alvarado and others, they well deserve the scientific consideration of antiquarians.” —From John Baily’s “Central America," published in 1850.

“Yucatan is the grave of a great nation that has mysteriously passed away and left behind no history. Every forest embosoms the majestic remains of vast temples, sculptured over with symbols of a lost creed, and noble cities, whose stately palaces and causeways attest in their mournful abandonment the colossal grandeur of their builders. They are the gigantic tombs of an illustrious race, but they bear neither name nor epitaph. The conscience-stricken awe with which the Indian avoids them as he relates a confused tradition of a whole people extinguished in blood and fire by his forefathers—a ferocious and cannibal race delighting in human sacrifices—are all that even conjecture can say of the manner in which the ancient occupants of Yucatan were blotted, en masse, from the page of existence. The barbarous exterminators remained the masters of the country, and built them rude huts under the shadow of those immense edifices which are still the marvel and the mystery of Yucatan. On many of these singular edifices is stamped the blood-red impress of a human hand—a fit symbol of the rule of blood to which it has so constantly been the victim. This ‘bloody hand’ was imprinted with evident purpose on the still yielding stucco of the new-built walls, and presents every line and curve in life-like distinctness: but the explanation of the symbol is unknown.”—New York Sun, June 8, 1848.

“In the shaft of J.L. Duncan and Co., on the ridge between the Middle and South Yubas, in this county, at the distance of 176 feet below the surface of the ground, was found, on the 26th of December, a curiously- fashioned glass bottle or jar, which was dug up in hard cement. After removing the reddish coating, an eighth of an inch thick, which attached to the outside, and thoroughly washing it, it was found to be of a light color and perfectly transparent. It somewhat resembled a small sized pickle-jar, but has a longer neck and a flat bottom. It must have been lying in the silent spot where it was found for many hundred years.”—Nevada Journal.

“Several specimens of American antiquities have recently arrived in this city. They were discovered by an American traveler whilst exploring the country of the Sierra Madre, near San Luis Potosi, Mexico, and excavated from the ruins of an ancient city, the existence of which is wholly unknown to the present inhabitants, either by tradition or history. They comprise two idols and a sacrificial basin, hewn from solid blocks of concrete sandstone, and are now in a most perfect state of preservation. … The sacrificial basin measures two feet in diameter, and displays much skill and truth in the workmanship. It is held by two serpents entwined, with their heads reversed,— the symbol of eternity, which enters largely into the mythology of the ancient Egyptians.”—St. Louis Weekly Union, December 29, 1849.

“Amongst the monuments of ancient architecture which are extant in the Mexican empire, the edifices of Mictlan in Mizteca, are very celebrated. There are many things about them worthy of admiration, particularly a large hall, the roof of which is supported by various cylindrical columns of stone 80 feet high, and about 20 in circumference, each of them consisting of one single piece. . . The gems most common among the Mexicans were emeralds, amethysts, cornelians, turquoises, and some others not known in Europe. Emeralds were so common that no lord or noble wanted them. … An infinite number of them were sent to the Court of Spain in the first year after the Conquest.”—From the Abbé Clavigero's History of Mexico, translated by Cullen, and published in London in 1787.

“Every one is in admiration of this beautiful region. No doubt this country has been inhabited; for we find evidences of a population more industrious, more civilized, and more docile than the rascally Apaches who now infest it. … This valley, like every other capable of being cultivated, gives evidence of a former people, agricultural in their pursuits, and no doubt far more civilized than the present race who desolate it.”—Captain Bonneville's Report of the Gila Expedition.

“I must not, however, forget to mention that there has lately been discovered, in the province of Vera Paz, 150 miles north-east of Guatemala, buried in a dense forest, and far from any settlements, a ruined city, surpassing Copan or Palenque in extent and magnificence, and displaying a degree of art to which none of the structures of Yucatan can lay claim?—From a letter by Mr. E.G. Squier, read before the American Ethnological Society, October 17, 1849.

ANCIENT COINS AND IMPLEMENTS.

“While some hands were digging out a cellar in Botetourt County, Va., they came upon a quantity of coin, consisting of some eight pieces, in an iron box about 14 inches square. The coin was larger than a dollar, and the inscription in a language wholly unknown to any person in the vicinity. Upon digging down some 16 inches lower, they came to a quantity of iron implements of singular and heretofore unseen shape. Several scientific gentlemen have examined into the matter, and had come to the conclusion that the coins, together with the other curiosities, must have been placed there at an extremely early date, and before the settlement of the country.”—New York Despatch.

“We have now in our possession, for safe keeping, and as a nucleus of a collection of curiosities, some very curious and singular articles made of copper. They were found near the west shore of the river, about a mile above the mouth, at a place where now is a brick-yard; and these were disinterred by those digging in search of good brick clay. After taking off from the surface of the ground about two feet of sand, the clay was exposed and the stump of a tree was discovered. Digging still lower about six or seven inches into the clay, and overturning the stump, these articles were brought to light:—First, a copper spear, about 14 inches in length; and at its base a groove or dovetail is made, in which to insert a wooden shaft or handle. Two other spears, each about 12 inches in length, and similar to the first. Third, two pieces of copper that had evidently been very nicely forged: but for what purposes they could ever have been applied is by no means plain; and it is quite difficult to give in writing a clear description of them. These are about 14 inches long and two inches wide. Upon one end there is the appearance of an attempt to make a cutting edge. They weigh about three pounds each, and are specimens of good workmanship. That these tools are the work of those who lived here years ago seems the more likely from the place and position in which they were found, being in the strata of clay, lying under the roots of a stump, and about 40 feet above the present level of the river and lake. The tree had grown up since these articles had been put there, and the deposit of sand made above the clay the depth of two feet. To do that, the river and lake must have been 40 feet higher than its present level. This, of course, was years ago, before the memory of the present races now inhabiting this country. Together with these tools was found scraps of copper, as though fragments left at the time of the manufacture of the tools.”—Lake Superior Mining News, December 21, 1854.

“Humboldt states that fragments of ancient painted pottery are found in the woods of both Americas, far from the residence of man. exhibiting crocodiles, monkeys, and some large quadrupeds. … The ancient fortifications found in the American forests are judged, by the trees, to be much above 1,000 years old. … The stone mountain in Carolina is a vast wall of stones, built by an extinct people. … In the plains of Varinas, South America, are found tumuli and a causeway, 13 miles long and 15 feet high, more ancient than the Indians. On the high rocks of Encaramada are sculptured and painted rocks; and also others on a large rock in the plains, which the Indians say were made by their fathers when the great waters lifted their boats to those levels. … The ruins of an ancient city, called Palangal, of great extent and high finish, have been discovered by Goo Galinda, in a thick forest near Poten, in the vicinity of the Missouri; and the neighboring country is also filled with architectural works. These and other remains in North America and the city lately discovered in Guatemala seem to prove revolutions of which we have no present suspicion.”—Extract from the writing of Sir R. Phillips.

“I reached the Gila in the valley, the lower end of which was out of sight, but evidently from 25 to 30 miles long, and from three to five wide. The soil is rich and lies well for irrigation. There was enough arable land passed through to support 20,000 people surrounded by fine prairie for grazing. Broken pottery was everywhere so plentiful that it amounts to a puzzle. A great many ruins, some of large villages or pueblos, are to be seen, and at points the marks of what must once have been a noble acequia, cut through such hard, strong banks, that it is difficult to believe no iron was used in the construction. The Pima Indians say these were the homes of their ancestors.”—Captain Ewell’s Report of the Gila Exploring Expedition.

“In removing the earth composing an ancient mound in the streets of Marietta, [Ohio,] on the margin of the plain, near the fortifications, several curious articles were discovered. They appear to have been buried with the body of the person to whose memory the mound was erected. Lying immediately over or on the forehead of the body, were found three large circular bosses or ornaments for a sword-belt or a buckler: they are composed of copper overlaid with a thick plate of silver. The fronts are slightly convex with a depression like a cup in the centre, and measure two inches and a quarter across the face of each. On the back side, opposite the depressed portion, is a copper rivet or nail, around which are two separate plates, by which they were fastened to the leather. Two small pieces of the leather were found lying between the plates of one of these bosses. They resemble the skin of a mummy, and seem to have been preserved by the salts of copper. The copper plates are nearly reduced to an oxide, or rust. The silver looks quite black, but is not much corroded, and in rubbing is quite brilliant. Two of these are yet entire; the third one is so much wasted that it dropped in pieces in removing it from the earth. Around the rivets of one of them is a small quantity of flax or hemp, in a tolerable state of preservation. Near the side of the body was found a plate of silver, which appears to have been the upper part of a sword-scabbard: it is six inches in length and two inches in breadth, and weighs one ounce. It has no ornaments or figures, but has three longitudinal ridges, which probably corresponded with the edges or ridges of the sword. It seems to have been fastened to the scabbard by three or four rivets, the holes of which remain in the silver. Two or three broken pieces of a copper tube were also found filled with iron rust. These pieces, from their appearance, composed the lower end of the scabbard, near the point of the sword. No signs of the sword itself were discovered, except the appearance of rust above mentioned. Near the feet was found a [round] piece of copper weighing three ounces. … It [the mound] has every appearance of being as old as any in the neighborhood, and was, at the first settlement of Marietta, covered with large trees. … The bones were much decayed, and many of them crumbled to dust on exposure to the air.”—From a letter by Dr. S.P. Hildred to the President of the American Antiquarian Society, dated “Marietta, November 3, 1819.”

“The news from the recently-discovered graves, in Chiriqui, is exciting and interesting. Images continued to be disinterred in large quantities. The value of those already exhumed could not be accurately estimated, as the natives hoarded up all they could get possession of, in order to obtain the highest possible price for them. Some think that there has been gold dug out to the amount of $150,000, while others estimate it double that sum. Antiquarians would find a rich field for research in Chiriqui; and it is to be regretted that all who are rushing thither look at these images in a light so intensely practical.”—From a letter by the New York correspondent of the London Daily Telegraph, printed in that paper, September 13, 1859.

[To be continued.]

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.