Magazine

Authenticity of the Book of Mormon

Title

Authenticity of the Book of Mormon

Magazine

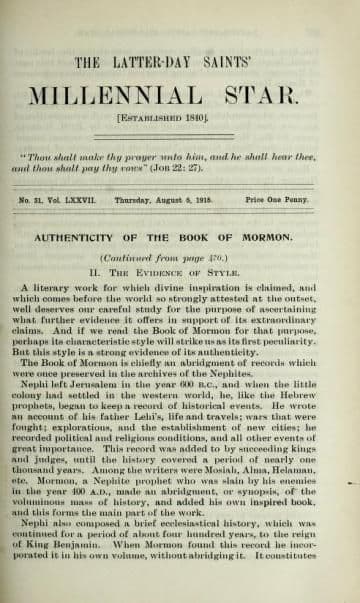

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1915

Authors

Sjodahl, J.M. (Primary)

Pagination

481–487

Date Published

5 August 1915

Volume

77

Issue Number

31

Abstract

In this series, Sjodahl wishes to convince the reader that the Book of Mormon is authentic by using historical, linguistic, and archaeological evidence, plus the testimonies of the eleven witnesses and examples of biblical scriptures that have been fulfilled through the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon is a “good book” that leads people to improve themselves and their lives. The second part considers the style(s) of the Book of Mormon and Hebrew transliterations.

AUTHENTICITY OF THE BOOK OF MORMON.

(Continued from page 470.)

II. The Evidence of Style.

A literary work for which divine inspiration is claimed, and which comes before the world so strongly attested at the outset, well deserves our careful study for the purpose of ascertaining what further evidence it offers in support of its extraordinary claims. And if we read the Book of Mormon for that purpose, perhaps its characteristic style will strike us as its first peculiarity. But this style is a strong evidence of its authenticity.

The Book of Mormon is chiefly an abridgment of records which were once preserved in the archives of the Nephites.

Nephi left Jerusalem in the year 600 B.C., and when the little colony had settled in the western world, he, like the Hebrew prophets, began to keep a record of historical events. He wrote an account of his father Lehi’s, life and travels; wars that were fought; explorations, and the establishment of new cities; he recorded political and religious conditions, and all other events of great importance. This record was added to by succeeding kings and judges, until the history covered a period of nearly one thousand years. Among the writers were Mosiah, Alma, Helaman, etc. Mormon, a Nephite prophet who was slain by his enemies in the year 400 A.D., made an abridgment, or synopsis, of" the voluminous mass of history, and added his own inspired book, and this forms the main part of the work.

Nephi also composed a brief ecclesiastical history, which was continued for a period of about four hundred years, to the reign of King Benjamin. When Mormon found this record he incorporated it in his own volume, without abridging it. It constitutes the first part of the English version, comprising the books of Nephi, Jacob, Enos, Jarom, and Omni, the translation of this part of Mormon’s abridgment having been lost through the carelessness of Martin Harris.

The abridgment of the last part of the volume, from the 8th chapter of the Book of Mormon, is the work of Moroni, the son of Mormon, who completed the entire collection with a composition of his own (See The Restoration of the Gospel, by B.H. Roberts, pages 286-90). Moroni also wrote an account of the ancient inhabitants of the “North Country,” based on the contents of twenty- four plates known as the Book of Ether.

Both in the briefer history of Nephi and the abridgment by Mormon, there are extensive quotations from the early prophetic writers of the Old Testament, this being possible because Lehi had a copy of the sacred scriptures, as extant at his time.

The English version is the translation of Joseph Smith, who, however, in the rendering of the Old Testament quotations, seems to have followed King James’ excellent version as closely as faithfulness to the text on the plates would permit. The Book of Mormon had only one translator, while the accepted Bible translations generally were the work of many scholars co-operating.

Such is the construction of the Book of Mormon, and its style, its literary peculiarities, are just what might be expected in a work of such origin. There is a certain similarity in expression and construction of sentences, due to the fact that it is, as we have stated, in its abridged form, principally the product of one pen, the author of the synopsis of the various larger records, and one translator; and also to another obvious fact, viz., that the records of Nephi undoubtedly formed the literary pattern of all subsequent writers who added their compositions to the collection. But there are also differences which, notwithstanding the smoothing and levelling effect of the work of the translator, appear clearly enough to suggest different original authors.

Read, for instance, the following from the opening chapter of I. Nephi:

“Yea, I make a record in the language of mv father, which consists of the learning of the Jews and the language of the Egyptians. And I know that the record which I make is true; and I make it with mine own hand; and I make it according to my knowledge.”

Note the tendency to repetition. Take another passage selected at random:

“And it came to pass that the Lord commanded me, wherefore I did make plates of ore, that I might engraven upon them the record of my people. And upon plates which I made, I did engraven the record of my father, and also our journeyings in the wilderness, and the prophecies of my father,” etc., (I. Nephi 19:1).

In the synopsis by Mormon this tendency to repetition is almost entirely absent. This peculiarity of style was, in all probability, even more conspicuous in the original than it is in the English translation.

Further, Mormon employs expressions which are not used by Nephi. One of these is “bands of death”; another, “sting of death” (Mos. 15:8, 9, 20, 23; 16:7. Alma 4:14; 5:7, 9, 10; 7:12; 11:41; 22:14. Mos. 16:7, 8. Alma 22:14). Nephi uses the expression “hard things” for difficult to understand, or to bear patiently (I. Nephi 3:5; 16:1, 2, 3; II. Nephi 9:40; 25:1), and this expression is peculiar to that part of the volume.

Again, “Great Spirit” as a name for God is peculiar to Mormon’s synopsis of the Book of Alma (Alma 18:2-5; 19:25, 27; 22:9-11), while “monster” and “awful monster” are peculiar to Nephi as referring to the adversary, or death and the grave (II. Nephi 9:10, 19, 26). Mormon uses that word in a different sense (Alma 19:26). And so does Moroni (Ether 6:10).

Such differences—and they are numerous—indicate that the book is the work of different authors, as claimed.

The Book of Mormon was written by men of Jewish descent, Nephi came from Jerusalem. In the Jewish Scriptures his native country is called Canaan, from a grandson of Noah (Ex. 15:15; Gen. 12:5); it is called Israel (Lev. 20:2); Judah (Ps. 76:1); Palestina, from the Philistines (Ex. 15:14; Isa. 14:29, 31). It is also called the “Land of Promise,” the “Land of God,” and the “Holy Land.” But in the Book of Mormon the favorite name is, the “Land of Jerusalem,” that is, the land in which Jerusalem was the chief city. It occurs about forty times, and is found both in the unabridged record of Nephi, and in the abridgments by Mormon and Moroni. This is just what might be expected from Nephi and his successors. For, to Nephi the most prominent part of his native country was Jerusalem. It was to him and his descendants, not the land of Canaan, or the land of Israel, or the land of the Philistines, but the land of Jerusalem, the city of God and of his ancestors; the city where all the memories of his childhood and the beginning of his marvelous mission centered. A modern writer would naturally have called the country by its common name, Palestine, and not by a strange name.

Another evidence of the Hebrew origin of the authors of the Book of Mormon is found in their religious ideas. One instance may be referred to. The Old Testament writers know of no “hell” such as depicted in modern times. They speak of Sheol, which means the grave, and the state of the dead. To the Prophet Jonah the mouth, or the belly, of the fish was “hell,” for he says he cried to the Lord out of “the belly of hell” (Jonah 2:2). The Old Testament idea of Sheol is predominant in the Book of Mormon, wherever “hell” is spoken of. (See, for instance, I. Nephi 15:26-36). Note especially verse 35:35:

“And there is a place prepared, yea, even that awful hell of which I have spoken, and the devil is the foundation of it; wherefore the final state of the souls of men is to dwell in the kingdom of God, or to be cast out.”

Blessedness, as well as misery hereafter, is a “state” of the soul.

Further corroborative evidence is found in the fact that, “In the parts of the Book of Mormon translated from the ‘smaller plates’ of Nephi, we find none of those comments or annotations mixed up with the record that we have already spoken of as being peculiar to the abridgment made by Mormon—a circumstance, we take it, which proves the Book of Mormon to be consistent with the account given of the original records from which it was translated” (B.H. Roberts, Outlines of-Ecclesiastical History, page 290). This is strong evidence, indeed, for the truth of the claims made for the Book of Mormon.

There is another line of evidence suggested by the literary style. The Book of Mormon has a more limited vocabulary than the Bible, and many important words appear very frequently. There are few poetic flights, such as meet us in some of the Hebrew prophets, and the language is less terse. But this is a very strong evidence in favor of the Book.

The Hebrew language, the language of Nephi, reached its golden age about the time of David. Isaiah, Micah, Nahum, Habbakuk, and Obadiah are said to write in a remarkably pure and elegant style, though foreign forms of speech (chiefly Aramean) are noted in Isaiah and Micah. After the time of Jeremiah there was a decline in literary elegance and vigor.

Nephi left Jerusalem at that time. He was a young man then, and the duties he was called upon to perform were of such a nature as to leave him but little opportunity for the development of literary talent. The later history of the descendants of the first colony was full of war and strife. The most elegant literary productions do not grow in fields over which armies march and war steeds incessantly trample. Mormon and Moroni were soldiers as well as prophets. They were born and reared among the tumultuous scenes immediately preceding the final overthrow of the Nephite commonwealth and the all but total extinction of the race. The general literary style of the Book of Mormon is just what might be expected when the history and the circumstances under which the authors wrote are considered, and they were aware of their limitations. Moroni says, “When we write, we behold our weakness, and stumble because of the placing of our words” (Ether 12:25). In clearness, however, and in delicacy of expression, they are not inferior to the authors of the Bible. They do not leave the reader in doubt as to the doctrines they expound, and they are entirely free from the use of words which render many scripture passages unfit for public reading in modern times. They sometimes write with pathos, tenderness, and sympathy, recalling, in this respect, passages in Jeremiah, the contemporary of Lehi, the father of Nephi. All this is very strong corroborative evidence.

III. Words and Phrases.

Nephi was taught in the learning of his father, who, like all educated Jews, knew Egyptian as well as Hebrew, and he wrote in the language of his father, which, he adds, consisted of the “learning” (vocabulary?) of the Jews and the “language” (letters) of the Egyptians. Do the writings of Nephi and his successors corroborate this statement? If so, this is the strongest evidence possible for the authenticity of those books.

This investigation is necessarily confined to a very limited area; for only few of the original words are retained in the translation. They are mostly proper names, some of which are found in the Bible. But there are others which are found in no other known record, and if these bear satisfactory evidence of Hebrew or Egyptian origin, they prove that the Book of Mormon was brought forth by divine power, for Joseph Smith knew neither Hebrew nor Egyptian at the time he translated that volume. It should be noted, however, that the transliteration from the language of the plates to English may not always reveal the precise original spelling. Anyone who has tried to render Hebrew or Arabian words into English letters will understand what is meant by this observation, for some of the letters in those languages have no equivalent in English, and the sounds they stand for can be but imperfectly indicated by the signs of our alphabet. The difficulty is similar to that which makes it almost impossible to indicate the correct pronunciation of French, Russian, or any other foreign language by the English letters. Similar difficulties Joseph must have encountered in transcribing names and words from the plates. This must be had in view when the untranslated words in the Book of Mormon are examined. The following are fair samples of Book of Mormon words:

Shazer. In I. Nephi 16:13, we read that Lehi and his little company, after having left their encampment and having followed the direction indicated to them for four days, came to a locality suitable for encampment and rest. They halted there long enough to replenish their food supply, and they called the place Shazer. This word is either the Hebrew Shazeh, gladness; or Chazer, which means green herbs. It indicates the pleasant, or verdant characteristics of their first encampment in the wilderness.

When Israel, after the exodus, had proceeded on their journey three days from the Red Sea, they came to a place where the water was so salty that they could not drink it. “Therefore the name of it was called Marah” (bitter). The place where Lehi encamped was green and pleasant. Therefore it was called Shazer. It was customary to name places according to their chief characteristics. Persons, too, were given names expressing qualities, experiences, or circumstances, as when Naomi said to her neighbors, “Call me not Naomi [beautiful], call me Mara [bitter].”[*]

Liahona. This is the name given, according to the Book of Alma (37:38), to the Ball, or Director, which Lehi found outside his tent door, and which had been prepared by the Lord to direct him in his journey through the wilderness. It is also called a “compass,” as the nearest modern equivalent of “liahona,” though that instrument was very different from a modern compass, since it operated only “according to the faith, and diligence, and heed which we did give unto them [the pointers]” (I. Nephi 16:28). This word is pure Hebrew, with the addition of a terminal «. It is composed of I, the preposition meaning “to”; Jah, the common abbreviation for Jehovah, and on, meaning “light.” On, it will be remembered, was the ancient name of Heliopolis, the city in Egypt in which the worship of the sun centered, and the birthplace of Joseph’s wife, Asenath. The word Liahona means, “To God is light!” That is to say, “God has light,” or, “From God comes light.” He is the Sun that gives light.

Lehi had just received the divine command to begin his perilous journey through the wilderness. One of the questions uppermost in his mind was, naturally, how to find the way. This must have been quite a problem. But he arose in the morning, determined to carry out the command of the Lord, undoubtedly having prayed for light and guidance. Standing in the tent door, looking, it may be, first, into the wide expanse before him; and then upon the camp around him, his attention was attracted by a metal ball “of curious workmanship.” He picked it up and examined it. And, as soon as he realized that it had been provided by his heavenly Father, in answer to his prayers, he exclaimed, full of joy and gratitude, L-jah-on “God has light!” “God gives light!” And this became the name of the instrument.

This manner of naming objects was a very ancient Semitic custom. When Hagar saw an angel by a spring in the wilderness, she exclaimed, “Thou God seest me!” And the spring was called, Beer-lahai-roi", i.e., “the well, to live, and to see,” or “the well of him that liveth and seeth me” (Gen. 16:14).

Lehi, therefore, conformed to an ancient custom in naming the God-sent Director, which seems to have operated, in response to his faith and diligence, on principles similar to those governing the use of the Urim and Thummim.

Deseret. This is a Jaredite word, meaning “honey bee.” It is copied from the Jaredite record, by Moroni, into his own synopsis of the Book of Ether (2:3).

In the Arabian language there is a word, aseleth, which means “honey.” The first letter of this word is a guttural for which we have no corresponding letter in the English alphabet. The letters “l” and “r” are interchangeable, as all who have heard Chinamen speak English know. The Arabian aseleth is, therefore, sufficiently similar to the Jaredite deseret to suggest a common origin. The Hebrew words asher (“happiness,” “blessedness”) and ashur (“one that is happy, prosperous”) maybe derived from the same root. The prosperity of the land of Canaan was indicated by the abundance of honey, among other things.

This is, of course, only a suggestion, but it is not very farfetched. The familiar word Gibraltar is from the Arabic, djebel-el-tarik. An “r” has taken the place of the “l,” just as in deseret. The word sugar is from the Hebrew shechar, from which there are many derivatives, including the Arabic sakar, the Persian shukkur and shukkur-kund (sugar-candy); the Indian jaggree, the Spanish azucar, and the Portuguese for “molasses,” mel-de-assucar. The name Amraphel (Gen. 14:9) is the same as the ancient Babylonian Hammurabi, and so on. I give these illustrations to show how words change in transmission from one language to another, and to prove that the suggestion that deseret, aseleth, asher, and ashur may have a common origin, is not improbable. If this conjecture is correct, the name Deseret, as applied to a country, would be identical with Assyria, which is a modern form of the Ashur of the Hebrews.

Mulek. In the Book of Mormon the infant soil of Zedekiah is called Mulek. He came from Jerusalem eleven years after Lehi. There is also a city of Mulek, and a missionary named Muloki. North America is called the land of Mulek, because the son of Zedekiah landed there. It is significant that in Egyptian inscriptions the name Juda-Malech is found, and that Dr. Birch identifies it with Jerusalem—Malech, being a term for royalty, and being of course, the same word as Mulek.

(TO BE CONTINUED.)

[*] Note the different spelling of the same word, Marah and Mara.

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.