Magazine

America's Ancient Inhabitants (23 October 1893)

Title

America's Ancient Inhabitants (23 October 1893)

Magazine

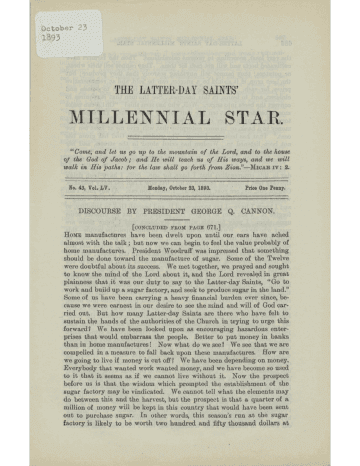

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1893

Authors

Ricks, Joel E. (Primary)

Pagination

695–698

Date Published

23 October 1893

Volume

55

Issue Number

43

Abstract

This series gives a report of the author’s explorations in Salt River Valley, Arizona, wherein he hypothesizes that the inhabitants of Salt River Valley came from Hagoth’s voyages to the north country (Alma 63). The peoples had buildings and temples made of cement and probably used metal. The second part gives Ricks' opinion of how the Salt River Valley civilization came to an end.

AMERICAS ANCIENT INHABITANTS.

[Continued from page 676.]

“Next in importance to the question of ‘Where they came from’ is the question of ‘What became of them?’ I have stood upon the old mounds and imagined myself upon some citadel or tower in the old city and have reconstructed all the buildings again, planted anew the fields, and covered the plain with a carpet of green, inhabited the buildings, and filled the streets with a bustling, busy population, and then I have asked myself the question: How could all this pass away?

“One evening I walked out to the ruins of an old temple. As I passed among the old buildings I frequently frightened the screech-owls from their perch on some high mound, and as I did so I could not help but think of that other civilization in the far east where the Euphrates flows calmly seaward. That city flourished cotemporaneously with this one. In its palmy days it was written of her: ‘But these two things shall come to thee in a moment, in one day the loss of children and widowhood. Desolation shall come upon thee suddenly. Thy astrologers and stargazers shall be as stubble; the fire shall burn them. Therefore the wild beasts of the desert with the wild beasts of the islands shall dwell there, and the owls shall dwell therein, and Babylon shall become heaps, a dwelling place for dragons, an astonishment and a hissing without an inhabitant.’

“If those words had been spoken over these old cities they would have been fulfilled almost literally, for almost every evidence here testifies of the sudden destruction that came upon them. If you dig into the ruins everything you encounter gives evidence that they were destroyed by fire. Underneath the fallen walls you find the skeletons of the former inhabitants mingled with the charred rafters of their buildings. It would seem that in the midst of their greatest development they were swept into eternity by the besom of destruction. The condition in which their canal system was left indicates that it was at its highest limit of perfection when abandoned. Through it the land had reached its highest limit of productiveness, and that to such a degree that it could have and must have, sustained hundreds of thousands. The ruins of the cities indicate no gradual decay before their abandonment, but everything points to a land prosperous and populous, from which, apparently in one single day, its people were swept like chaff from off the summer threshing-floor, leaving no history, no tradition. The dried-up canals, the ruined houses, alone remain to whisper the story of a people whose history perished with them; whose traditions no grey-haired sire ever relates to eager grandchildren; whose altars lie buried under the dust of centuries; whose ruined homes stand in the shadow of the mountains, untrod by mother or child for many generations; a people whose gods have boasted neither shrine nor worshipper since that day so many hundred years ago when the savage tribes of the mountains came down upon them, burned their cities, destroyed their canals, and swept from the earth a civilization, the most interesting and least known of all our pro-historic nations.

‘‘While the large majority of the ruins indicate a destruction at the hands of men there are one or two that would lead us to believe that nature had contributed to the woes of that unfortunate people. We are told that when Professor Cushing was here, the ruins of one of the cities he excavated gave evidence of having been destroyed by an earthquake. The walls had evidently been shaken down and he found the skeletons of several persons who were caught by the falling walls while trying to escape through a window, in another place lava streams have been found to cross the course of an old canal; and an olla, or crock jar and pestle were found 115 feet underground. These would indicate at least that at some time, during the residence here of the old people, the country had been visited by one of those great convulsions of nature that has upturned so much of this western country, at some remote period in the past, while it may be true that at some period some of the old cities were destroyed in this manner and by natural agencies, it is clear to any casual observer that the last great destruction was not brought about in that manner, earthquakes do not usually crack the skulls of their victims with war clubs, and burn the buildings over the heads of the slain.

“It is difficult at this late day to form a correct estimate of the degree of civilization attained by this old people. If we walk over the site of one of their cities, and pick up samples of the many pieces of pottery scattered about, or if you excavate into one of the mounds and find there stone implements and grinders, you are apt to say ‘This people was only partially advanced in the arts of civilized life; at best they can only be classed among the semi-civilized nations of the past.’ But when you examine more carefully the great works they accomplished you are filled with wonder and astonishment. Their canal system was indeed a remarkable one. The most skilled engineer of the present day armed with the most improved instruments known to science, can do no better than to follow the lines laid down by his pre-historic predecessor, so that every ditch, thus far built along the Salt and Gila Rivers, either runs parallel to or merges into, some ancient canal, while there are places which the older ditches irrigated, but which the present ones thus far have not been able to bring under water. Just out from Mesa a mile or two one of the old canals runs for some distance through a straight raise in the Mesa, where it was necessary for the builders to make an excavation to a considerable depth, to accomplish which they had to remove great quantities of cement rock .Now, all excavators know how difficult an undertaking it is to remove this kind of rock even with our modern appliances, but if you take away from us gunpowder and our other explosives by which we loosen and break up the rock it would puzzle our best engineers to-day to know how to remove any quantity of it with these facts before us, our wonder increases when we take from these ancient builders all knowledge of iron steel, copper, and in fact, any metal whatever and give them some rude stone hammers and mauls, and perhaps some wooden shovels, made of cottonwood or mesquit, and then try to imagine how they went to work to excavate this cement rock, which is even harder than their basalt implements. How did they do it? was the question that I asked several gentlemen. None of them could give a satisfactory answer. One gentleman gave it as his opinion that they had removed the dirt from the rock, and built fires on it, and, after heating it, dashed on water and in this way cracked it, after which it could be broken up and removed. I related this theory to two or three railroad contractors, who had had a great deal of experience in removing the same kind of material, and they were unanimous in the opinion that it could never have been removed in that manner; that the nature of the cement is such that fire and water would not have the effect upon it stated above. If this be true, then the question still remains unanswered. One gentleman told me he did not see how the old builders could have ever made the excavation with the rude instruments that they had, but they must have done it, as numbers of stone hammers and axes were scattered around the cut. This, I believe, is the general opinion among those who have given the matter any thought. For my part I see no very strong argument in the above. It is not improbable that the stone implements referred to could have been left there by a more recent people; still, even if they were left there by the builders themselves, as I believe, it does not argue that they had no other and far better implements to work with; no more than the discovery of numerous arrowheads of flint on the plains of Marathon would force us to the conclusion that the great armies who participated in that battle were armed with such rude instruments of war as this would indicate. We know from history just how these armies were armed; but suppose we had no history of those times, and were compelled to judge of the civilization of the old people by just such finds as that at Marathon— would we not place an estimate on it far below what it really deserved? It seems to me that that is just what all archaeologists are doing with our ancient American civilizations. They see about them stupendous works, such as the great roads of Peru, the great blocks of stone so beautifully wrought in Peru and Central America, these old canals and many other things that would seem to point to a degree of civilization equal to any of the civilizations of the east, and works, too, that seemingly would require tools of the best iron and steel to execute; yet, for all this, they say these metals were never known to the ancient people of this continent, for the reason that no traces of them are found; and they close their eyes to the fact that history records no such accomplishments by any other people without iron, and that it would seem impossible that it could be accomplished without that metal. They seem to forget that iron is the most perishable of all metals, that it rapidly oxidizes unless protected from air and moisture, and that, notwithstanding we know that the ancient Assyrians and Babylonians had great quantities of that metal, yet very few traces of it are now found in the ruins of their cities. Then, too, the fact should not be overlooked that in the ruins of people whose history we know, and who were experts in working iron, to-day large quantities of stone and flint implements are found, and which is accounted for on the basis that they were used by them for many purposes at the same time iron was. If, then, these facts are true of a people whose history we know, could not they be equally true of a people whose history we do not know, when all other conditions are equal?

“In a former letter we referred to the watch towers on the mountain peaks, where guards were maintained; this would indicate that the old people were accustomed to war. Indeed, it seems probable that for a long time they had to guard against invasion from the wild tribes that surrounded them. This being true we would naturally expect to find in the ruins of their cities some remains of their implements of war, just as we find in the old Mexican and Peruvian ruins large numbers of flint arrow-heads and spear-heads, and stones with sharp points, used on war clubs, and many other things to indicate the nature of the implements of war used by the old people. All who visit these ruins must be struck with the scarcity of these things. True, a few arrowheads are found, but not in numbers that would be expected if they were used to any extent. No other instruments of war have been found as far as I could learn. Had their implements of war been made of iron they must have all perished long ago, so that no trace of them would now remain. While we have no conclusive evidence on this point it is difficult for us to understand how they could accomplish the works that we see here without the aid of that important metal.

[To be continued.]

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.