Magazine

American Antiquities: Corroborative of the Book of Mormon (7 January 1860)

Title

American Antiquities: Corroborative of the Book of Mormon (7 January 1860)

Magazine

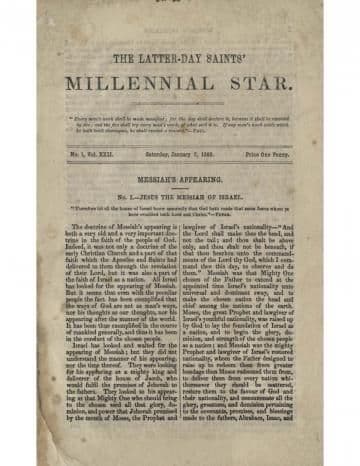

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1860

Editors

Lyman, Amasa (Secondary)

Pagination

13–14

Date Published

7 January 1860

Volume

22

Issue Number

1

Abstract

This 47-part series provides evidence to confirm the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. It describes the contents of the Book of Mormon and archaeological findings and discoveries, such as ancient cities, temples, altars, tools, and wells. Each part contains several excerpts from other publications that support the Book of Mormon.

AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES,

CORROBORATIVE OF THE BOOK OF MORMON.

(Continued from page 836, Vol. XXI.)

(From an American Paper.)

“Skeletons of men ten feet high have been discovered in a burying-ground about a mile north-west of Winchester, Indiana. They probably belonged to the ‘higher classes.’”

(From the Illinois Journal.)

“A subterranean vault has been discovered near Jackson, Illinois, in which the air is so mephitic that no man can go down into it. But, by means of rakes and hooks, human bones of a gigantic size have been drawn up from its depths, and also curious coins.”

(From a letter by the New York correspondent of the London Daily Telegraph, printed in that paper, Sept. 13, 1859.)

“The news from the recently- discovered graves, in Chiriqui, is exciting and interesting. Images continued to be disinterred in large quantities. The value of those already exhumed could not be accurately estimated, as the the natives hoarded up all they could get possession of, in order to obtain the highest possible price for them. Some think that there has been gold dug out to the amount of $150,000, while others estimate it at double that sum. Antiquarians would find a rich field for research in Chiriqui; and it is to be regretted that all who are rushing thither look at these images in a light so intensely practical.”

(From the Encyclopedia Britannica, 8th edition, published in 1853.)

“It is remarkable that the Mexican annals reach to a more remote date than those of any of the nations of northern Europe, though they were preserved merely by an imperfect species of hieroglyphics, or picture-writing. We do not pretend to enter into the question that may be raised, both as to the authenticity of the records themselves, and their susceptibility of a correct interpretation. It is enough that they have received credit from Humboldt, Vater, and other men of learning and judgment who have examined into their nature and origin. From the annals thus preserved, we learn that several nations belonging to one race migrated in succession from the north-west* and settled in Anahuac or Mexico. … The ancient empire of Peru, more extensive than that of Mexico, embraced the whole sea-coast from Pastos to the river Maule, a line of 2,500 miles in length. … Their masonry was superior to that of the Mexicans. Like the ancient Egyptians, they understood mechanics sufficiently to move stones of vast size, even of 30 feet in length, of which specimens are still existing in the walls of the fortress of Cusco. They had the art of squaring and cutting blocks for building with great accuracy. … They are joined with such nicety that the line which divides the blocks can scarcely be perceived; and the outer surface is in some cases covered with carving. … The ancient public roads of Peru are justly considered as striking monuments of the political genius of the government. One of these extended along the sides of the Andes from Quito to Cusco, a distance of 1,500 miles. It is about 40 feet broad, and paved with the earth and stones which were turned up from the soil; but in some marshy places it is formed, like the old Roman roads, of a compact body of solid masonry. …

They knew how to smelt and refine the silver ore, and they possessed the secret of giving great hardness and durability to copper by mixing it with tin. Their utensils and trinkets of gold and silver are said to be fashioned with neatness and even taste. … The llama, a species of camel, which they had tamed, was employed to some extent as a beast of burden. … For the purposes of police and civil jurisdiction, the people were divided into parties of ten families, like the tythings of Alfred, over each of which was an officer. A second class of officers had control over five or ten tythings; a third class over fifty or a hundred. These last rendered account to the Incas, who exercised a vigilant superintendence over the whole, and employed inspectors to visit the provinces, as a check upon mal-administration. Each of these officers, down to the lowest, judged, without appeal, in all differences that arose within his division, and enforced the laws of the empire, among which were some for punishing idleness, and compelling every one to labour. … The government of Peru was a theocracy. The Inca was at once the temporal sovereign and the supreme pontiff. He was regarded as the descendant and representative of the great Deity, the sun, who was supposed to inspire his counsels and speak through his orders and decrees. … The Inca not only assumed the title of the Father of his people, but the vices as well as the merits of his government sprung partly from the attempt made to construct the government on the model of paternal authority, and partly from the blending of moral and religious injunctions with civil duties. Hence the idle pretension of the state to reward virtuous conduct, as well as to punish crimes; hence, too, the plan of labouring in common, the extinction of individual property, the absurdities of eating, drinking, sleeping, tilling, building, according to fixed universal rules; in fine, that minute and vexatious regulation of all the acts of ordinary life, which converted the people into mere machines in the bands of an immense corps of civil and religious officers. … The government was as pure a despotism, probably, as ever existed; but its theocratical character, no doubt, helped to mitigate the ferocity of its spirit. … The cosmogony of the Mexicans has too many analogies with that of the Jews to admit of the coincidence befog accidental. Their traditions speak of the serpent woman, or the mother of mankind, falling from a state of innocence; of a great inundation, from which a single family escaped; of a pyramid raised by the pride of man, and destroyed by the anger of the gods. … In the great valley of the Mississippi and its mighty tributaries, the Ohio and Missouri, are the remains of the works of an extinct race of men, who seem to have made advances in civilisation far beyond the races of red men then discovered by the first European adventurers. These remains consist chiefly of tumuli and ramparts of earth, enclosing areas of great extent and much regularity of form. … The barrows and ramparts are constructed of mingled earth and stones; and, from their solidity and extent, must have required the labour of a numerous population, with leisure and skill sufficient to undertake combined and vast operations. The barrows often contain human bones, and the smaller tumuli appear to have been tombs; but the larger, especially the quadrangular mounds, would seem to have served as temples to the early inhabitants. These barrows vary in size, from a few feet in circumference and elevation to structures with a basal circumference of 1,000 or 2,000 feet, and an altitude of from 60 to 90 feet, resembling in dimensions the vast tumulus of Alyattes, near Sardis. One in Mississippi is said to cover a base of six acres. The ramparts also vary in thickness, and in height from 6 to 30 feet, and usually enclose areas varying from 100 to 200 acres. Some contain 400; and one on the Missouri has an area of 600 acres. The enclosures generally are very exact circles or squares,— sometimes a union of both; occasionally they form parallelograms, or follow the sinuosities of a hill; and in one district, that of Wisconsin, they assume the fanciful shape of men, quadrupeds, birds, or serpents. delineated with some ingenuity, on the surface of undulating plains or wide savannahs. These ramparts are usually placed on elevations or hills, or on the banks of streams, so as to show that they were erected for defensive purposes; and their sites are judiciously chosen for this end. … These remains are not solitary and few; for in the State of Ohio they amount to at least 10,000.”

(To be continued.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.