Share

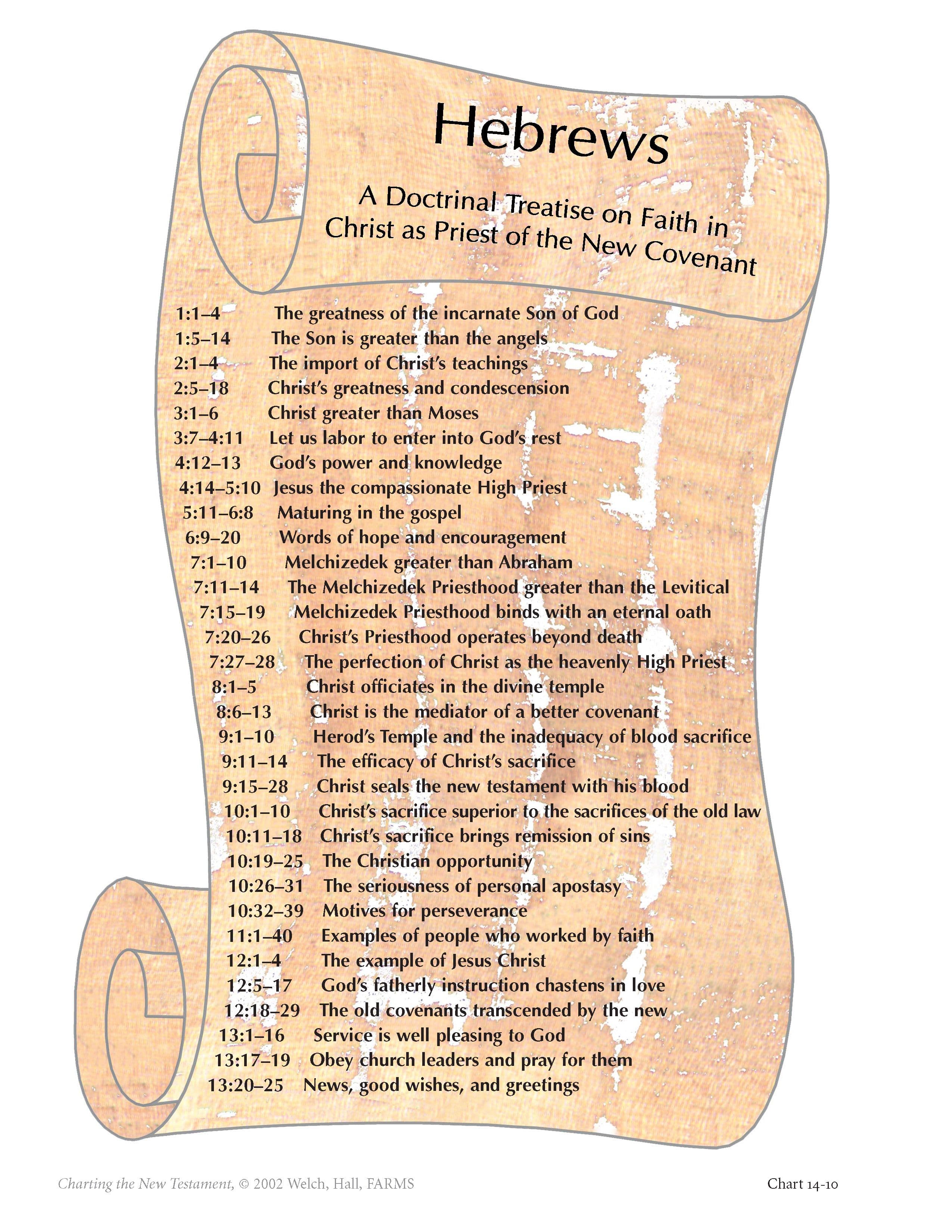

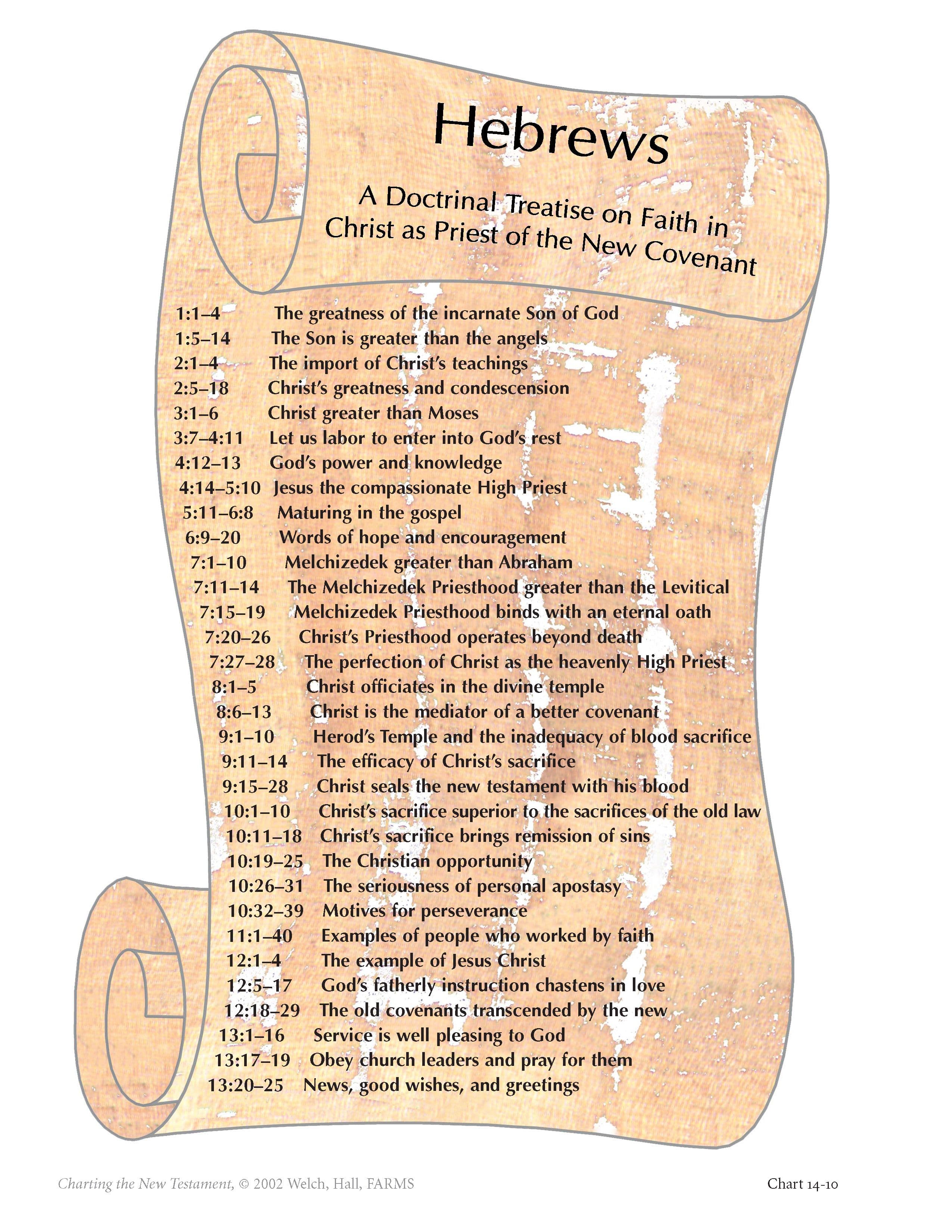

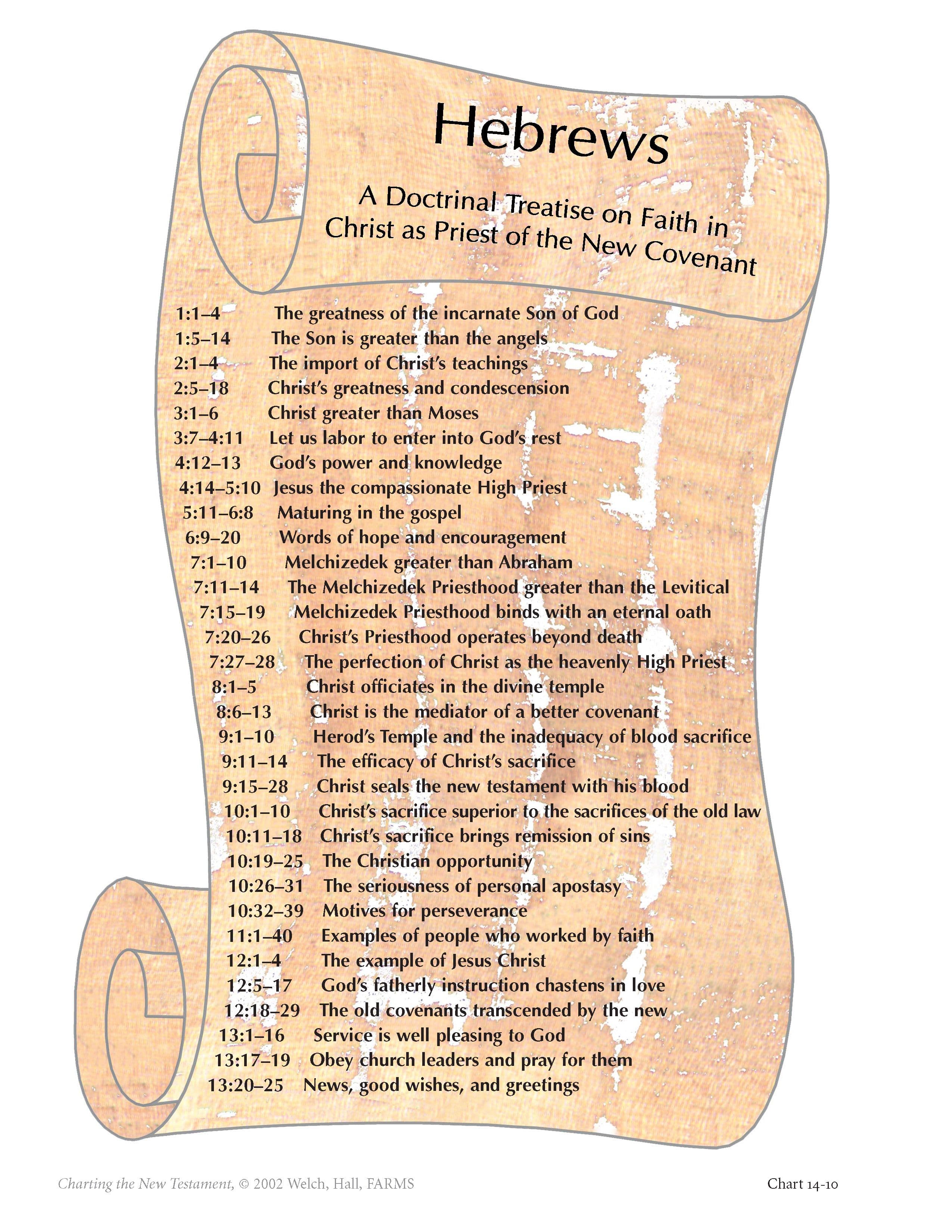

Hebrews

Title

Hebrews

Publication Type

Chart

Year of Publication

2002

Authors

Welch, John W. (Primary), and Hall, John F. (Primary)

Number

14-10

Publisher

Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies

City

Provo, UT

Share

Abstract

The following charts give an overview of each of the epistles in the New Testament. These twenty-one letters, among the most important ever written in the history of the world, were sent by Peter, James, John, Paul, and Jude to some of the earliest Christians.

Each chart divides the letter into thematic blocks with subheadings that outline the main contents of each block. By reading through the outline of each letter, readers can get a quick overview of each text. Used as a guide, each chart should help modern readers find their way through these letters, many of which are fairly complicated and sometimes obscure. A main purpose of these charts is to bring the messages of these letters to life by making the dominant purpose and underlying structure of each letter clear.

Most of these letters follow the pattern typically found in ancient letters. First, they begin with an introduction of greetings, salutations, or well-wishes. The New Testament letters, however, are unusually personal and religious. Next, they take time to reinforce the bonds of friendship, familiarity, loyalty, and personal concern. The body of each letter then deals with various topics: some are doctrinal; some are practical; others are filled with information or encouragement. Finally, they each conclude with farewell statements and extended greetings in accordance with standard epistolary practice.

Beyond formal similarities, however, it is important to note that each letter is addressed to a particular audience. Some congregations, such as in Corinth, were struggling with dissension; others, such as the community in Philippi, were thriving; some, like the church in Thessalonica, were new, while others, as at Rome, were well established. Thus, different levels of instruction are found in each of these letter. in addition, Paul knew some of his audiences better than others, and thus his degree of familiarity and friendship is much higher when he wrote to the Saints in Ephesus, for example, than when he expounded more abstract teachings to the Galatians. Likewise, Paul’s close working relationship with his convert Timothy explains the tone of paternal guidance found in his letters to Timothy, in contrast, for example, to the sterner tone of Jude’s letter of warning.

Under the name of each letter is a subtitle profiling and highlighting its dominant point or purpose. Hopefully, these subtitles and outlines will orient readers and students to the key characteristics of each letter. The charts are grouped approximately in chronological order.

Little is known about the time and place where the epistle to the Hebrews might have been written. Entertaining the possibility that it was written or coauthored by Paul during his prolonged house arrest in Caesarea helps to see it as a doctrinal treatise, addressed to people in Judea, establishing the importance of faith in Jesus Christ as the priest of the new covenant. Paul had tried to take gentile converts into the Temple of Jerusalem, believing that the atonement of Jesus had opened the blessings of the covenant to all people. As chart 14-10 clarifies, each part of this letter serves to explain and bolster the Christian claims that stood behind the uproar in Jerusalem that led to Paul being taken into custody.

Subject Keywords

Study Helps

Pauline Epistles

Epistle to the Hebrews

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.