KnoWhy #826 | November 20, 2025

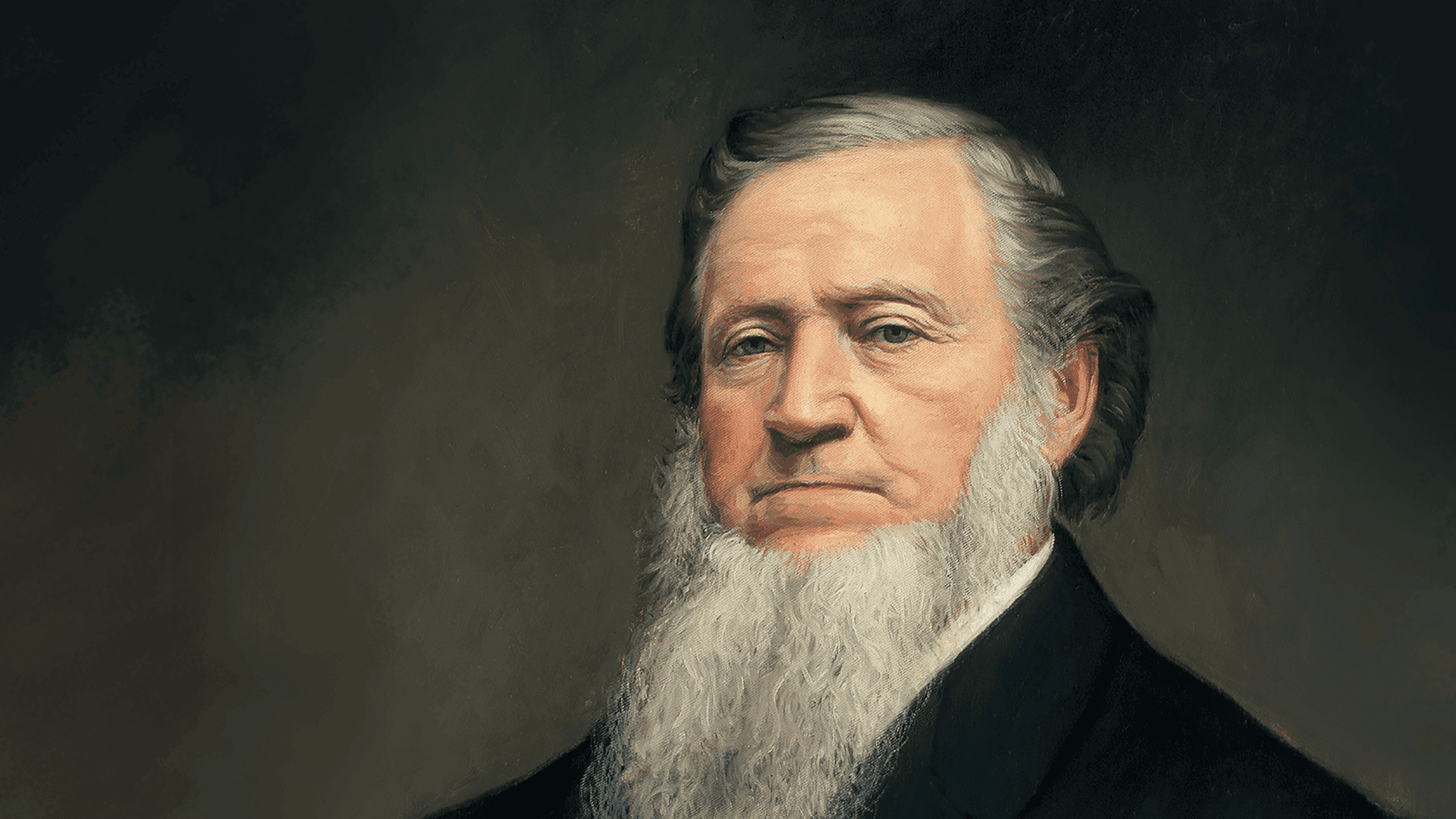

Why Did the Mantle of Joseph Smith Fall on Brigham Young?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Let the companies be organized with captains of hundreds, captains of fifties, and captains of tens, with a president and his two counselors at their head, under the direction of the Twelve Apostles. Doctrine and Covenants 136:3

The Know

On August 8, 1844, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints gathered for what would be one of the most important and influential meetings in their history. Just six weeks earlier, on June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum had been murdered in Carthage Jail, and many Saints wondered who would fill the position of their beloved Prophet. Although other contenders for Joseph’s position would later arise, the six days in August (specifically August 3–8), which would later become known among some historians as the “succession crisis,” focused at first only on two candidates: Sidney Rigdon and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Sidney Rigdon had been a counselor in the First Presidency (which was dissolved when Joseph died). However, from the time of the Saints’ arrival in Illinois in 1839, Sidney had steadily lost the confidence of Joseph Smith. Sidney disagreed adamantly with Joseph on gathering the Saints as a large body in Nauvoo, and also did not accept Joseph’s restoration of temple ordinances or other practices, including plural marriage. Furthermore, “despite formally being a counselor to Joseph Smith in the First Presidency,” as Ronald K. Esplin has observed, Rigdon did not “ever fully function as a counselor in Nauvoo as he had in Kirtland and in Missouri.” Until 1843, Sidney was known in Nauvoo for being aloof from the Church, not attending councils, not being always healthy, and attending mainly to his own personal affairs.1 In October 1843, Rigdon’s lack of commitment to his position and the Church led Joseph Smith to call for his removal from the First Presidency, but the vote of the Church through the law of common consent allowed Sidney to maintain his position. However, Sidney remained an ineffective counselor to Joseph.2 He eventually moved back to his former home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at the request of Joseph Smith and the Council of Fifty, to serve in that area and to be Joseph’s vice-presidential running mate for the presidency of the United States.3 Furthermore, despite being in the First Presidency of the Church, Sidney had never received all the keys of the Priesthood that Joseph had. It would appear that before March 1844 only Joseph and Hyrum Smith held all of those keys (see particularly Doctrine and Covenants 124:93–96).4

The Twelve Apostles, on the other hand, were Joseph’s closest advisors during the last few years of his life.5 Having continually proved their loyalty to Joseph Smith, the Quorum of the Twelve were never more united under the leadership of Brigham Young. While the First Presidency was imprisoned in Missouri, it was the Apostles who took lead of the Church’s exodus to Illinois, and it was the Twelve who sought to see the Lord’s command to leave on a mission to England from Far West fulfilled even at risk to their lives.6 After they returned from that mission, Joseph publicly declared to the Church, “the time had come when the twelve should be called upon to stand in their place next to the first presidency … as they had been faithful and had borne the burden in the heat of the day.”7 This was in line with what a former revelation had clearly stated, namely that the Twelve, as a quorum, were “equal in authority and power to the three presidents” in the First Presidency (Doctrine and Covenants 107:24), and thus would hold all the necessary keys should the quorum of the First Presidency be dissolved.

Indeed, “Over the next nearly three years, no important church-related initiative was undertaken by the Presidency (increasingly Joseph and Hyrum, not William Law or Sidney Rigdon) without Brigham Young and the Twelve at their side.”8 Many in the Church even noted that the Apostle Amasa Lyman was placed in the First Presidency to replace Sidney for his ineffectiveness and soon became the only functioning counselor to Joseph and Hyrum.9 Then, in March 1844, realizing that his death was perilously close, Joseph gathered nine of the twelve apostles and gave them his “last charge” as well as rolling off upon them the full keys of the kingdom held by himself and his brother, Hyrum.10 Because of these keys, the Twelve “had full confidence that they alone held all the necessary keys. It was this knowledge, to Young this reality, that fueled their leadership. That reality also kept them focused on building on the foundation Joseph laid.”11

In addition to possessing all the keys that had been restored especially by Peter, James, John, Moses, Elijah, Elias, and Jesus Christ, Joseph had plainly taught almost a decade earlier that apostles had the unique responsibility to preside where there was no presidency and to build up a kingdom until they had appointed high priests over it.12 With the death of Joseph Smith, the First Presidency was dissolved. Since the Apostles preside where there is no presidency, that power and responsibility fell exclusively to them to reconstitute the First Presidency as the presiding high priests of the Church, then to be sustained by the full membership of the Church (Doctrine and Covenants 107:22).

All of this came to a head early in August 1844, when Rigdon and the traveling Apostles had all returned to Nauvoo. Rigdon began to argue that there could be no prophet after Joseph and that he should become a “guardian” over the Church. Rigdon was supported by William Marks, the stake president of Nauvoo, who likewise did not support the building of the temple or Joseph’s revelation (see D&C 132) on sacred plural marriage for time and eternity. Secretly, Rigdon also met with many of the Saints and began claiming that Joseph was a fallen prophet and threatened that, if he was not called to lead, he would expose the Church’s supposedly dark secrets.13 The Twelve’s position, however, was different: they had been endowed and held the keys of the Priesthood. They had been called by Joseph to stand next to him in authority, and the Saints knew and respected the Twelve for their leadership and were also aware of Sidney’s shortcomings and refusal to take part in the Church. So, on August 8, 1844, the Church—almost unanimously—voted to follow the Twelve rather than Sidney.14 Based on the law of common consent, the same law that had previously allowed Sidney to maintain his position as a counselor to Joseph, the Twelve now would lead the Church following Joseph’s death.15 Though the Twelve emphatically stated that Sidney could continually have a place in the Church, Sidney continued to claim that he should be chosen as the leader of the Church. 16

But then, as evidence of the Lord’s calling of Brigham Young, many Saints who had gathered for that meeting in Nauvoo experienced an important miracle,. After Sidney had made his final pitch, Brigham stood, and while he spoke many in the congregation saw or heard Joseph Smith in his place. More than one hundred witnesses, for the rest of their lives, would personally testify that they had seen and/or heard the mantle of Joseph Smith fall on Brigham Young that day.17 These types of manifestations not only occurred during that August 8 meeting, but at various subsequent times as well.18 This miracle was never used as the governing reason why the Twelve should lead the Church. Rather, the Lord’s revelations regarding Church organization and the Law of Common Consent had already established the pattern that the Apostles followed. This miracle did, however, provide for many of the Saints a signficant spiritual confirmation in those processes.19 As Wilford Woodruff taught, “There was a reason for this [miracle] in the mind of God: it convinced the people. They saw and heard for themselves, and it was by the power of God.”20

Evidence that this miracle had happened was so strong even those who followed other false prophets were aware that something had happened on that day. Indeed, in 1855, William Hickenlooper wrote a letter to his son and daughter who were deciding to follow James Strang (who later claimed to be Joseph’s successor with a forged letter), in which Hickenlooper explained to them that he had been a witness to the transfiguration of Brigham Young. Hickenlooper’s son-in-law publicly responded, trying to explain this miracle away, through naturalistic means. That letter shows that the transfiguration was known to both supporters and opponents of Brigham Young early on.21

The Why

Although the succession crisis had quickly ended with the Saints’ virtually unanimous support for Brigham Young, Sidney—who had not seen the transfiguration—persisted in trying to gain a following before his excommunication. In addition, other individuals would in subsequent months and years would also try to claim that they were actually the rightful successors to Joseph Smith, though their own claims were often even less acceptable to most people than Rigdon’s claims had been.22 Of those individuals, Esplin observed, “Most of the minority who sought an alternative to the Twelve did so less from a quarrel with the claims Young and the Twelve made to have authority from Joseph, but because they had a quarrel with the program.”23 While most of those individuals still loved the Book of Mormon, they mainly wanted to distance themselves from the temple, from the whole concept of eternal marriage, and from several other teachings of Joseph that they did not like.24

The same, however, was not true for Brigham Young and the Twelve Apostles. Speaking to the Council of Fifty in March 1845, Brigham declared, “To carry out Josephs measures is sweeter to me than the honey or the honey comb.”25 In the October 1844 General Conference of the Church, Brigham Young stated, “It is the test of our fellowship to believe and confess that Joseph lived and died a prophet of God in good standing,” and testified that the Church would continue on exactly as it had been restored through Joseph Smith, the Lord’s first prophet in this last dispensation of the gospel of Jesus Christ.26

As Esplin observed, “Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve were the only ones on the ground in Nauvoo in 1844 with a plausible claim to lead—because Joseph Smith had prepared them and had given them all the priesthood keys and authority needed to do so in his absence. No one else held all the keys, no one else had the confidence of most of the people, no one else knew the full program in detail, and therefore no one seriously challenged their leadership.”27 Under the direction of the Twelve Apostles, the Church was able to survive, as the Lord had already revealed and established, particularly in D&C 107, the means and manner in which each succeeding president and prophet of the Church was to be called. Today, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints still follows this practice of apostolic succession, with the senior apostle becoming the next prophet, seer, and revelator.

Though not all cases of apostolic succession have been coupled with such a divine outpouring of the spirit as was Brigham Young’s, wherein he was transfigured to look and sound like Joseph Smith for many in the congregation on August 8 and on other occasions, each prophet is called and confirmed according to these well-established patterns. Because Brigham Young was the first prophet to succeed his predecessor, it may well be that this unusual miraculous mantle experience happened largely to comfort the people during that time of tragic loss and also to help confirm that the Church would continue. “Succession was painful. Losing Joseph was catastrophic. Moving forward was difficult. But not only did the Church and the priesthood and the ordinances survive under Brigham Young and the Twelve, they thrived.”28

Ronald K. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph’: A Detailed Exploration of the 1844 Succession,” in Joseph Smith: A Life Lived in Crescendo, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2024), 745–882.

R. Jean Addams, “Aftermath of the Martyrdom: Aspirants to the Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” in Joseph Smith: A Life Lived in Crescendo, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2024), 977–1050.

“Documents of Testimonies of the Mantle Experience,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820-1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed. (BYU Studies, 2017), 430–504.

Lynne Watkins Jorgensen, “The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Passes to Brother Brigham: One Hundred Twenty-nine Testimonies of a Collective Spiritual Witness,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820-1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed. (BYU Studies, 2017), 394–429.

Ronald W. Walker, “Six Days in August: Brigham Young and the Succession,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, ed. David J. Whittaker and Arnold K. Garr (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2011), 161–96.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Alexander L. Baugh, “‘I Roll the Burthen and Responsibility of Leading This Church Off from My Shoulders on to Yours’: The 1844/1845 Declaration of the Quorum of the Twelve Regarding Apostolic Succession,” BYU Studies 49, no. 3 (2010): 4–20.

Ronald K. Esplin, The Emergence of Brigham Young and the Twelve to Mormon Leadership, 1830–1841 (BYU Studies, 2006).

Andrew F. Ehat, Joseph Smith’s Introduction of Temple Ordinances and the 1844 Mormon Succession Question (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1982).

- 1. Ronald K. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph’: A Detailed Exploration of the 1844 Succession,” in Joseph Smith: A Life Lived in Crescendo, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2024), 763-64. This paper is greatly expanded from a previous publication by the author found in Ronald K. Esplin, “Joseph, Brigham and the Twelve: A Succession of Continuity,” BYU Studies 21, no. 3 (1981): 301–41.

- 2. According to Esplin, “The vote that October conference gave Sidney a second chance—but still he failed to fulfill his office. His own statements in April conference 1844 and abundant testimony at his public excommunication trial in September of that year confirmed that very little changed. He continued to be absent from leadership councils and failed to function as a counselor.” Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 765. Indeed, he only addressed the Saints publicly one time following the October conference. See also pp. 766–69.

- 3. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 770–71

- 4. For another summary of Sidney’s actions surrounding the succession crisis, see Ronald W. Walker, “Six Days in August: Brigham Young and the Succession,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, ed. David J. Whittaker and Arnold K. Garr (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2011), 162–69.

- 5. For an in-depth study on this, see Ronald K. Esplin, The Emergence of Brigham Young and the Twelve to Mormon Leadership, 1830–1841 (BYU Studies, 2006).

- 6. See Scripture Central, KnoWhy 817 ; Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 751–54.

- 7. “Discourse, 16 August 1841,” as Published in Times and Seasons, pp. 521–22, The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 8. Esplin “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 759.

- 9. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 769, 817.

- 10. Journal, December 1842–June 1844; Book 1, 21 December 1842–10 March 1843, p. 167, The Joseph Smith Papers. For Orson Pratt’s recollection of this event, see “Appendix 3: Orson Hyde, Statement about Quorum of the Twelve, circa Late March 1845,” p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers. For a very convenient and important discussion of this crucial event, see Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Alexander L. Baugh, “‘I Roll the Burthen and Responsibility of Leading This Church Off from My Shoulders on to Yours’: The 1844/1845 Declaration of the Quorum of the Twelve Regarding Apostolic Succession,” BYU Studies 49, no. 3 (2010): 4–20; and also Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “Dennison Lott Harris’s Firsthand Accounts of the Conspiracy of Nauvoo and the Transmission of Apostolic Keys,” in Joseph Smith: A Life Lived in Crescendo, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, vol. 2 (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2024), 883–976.

- 11. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 750. When he first heard about the death of Joseph, Brigham was worried about what they had lost before the inspiration struck him that the apostles had the keys, and the work of God could not be frustrated. See Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 775–76.

- 12. See John S. Thompson, “Restoring Melchizedek Priesthood,” in Joseph Smith: A Life Lived in Crescendo, 2 Vols., Ed. by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2024), 1:275-280; Casey Paul Griffiths, Scripture Central Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, vol. 3 (Cedar Fort, 2024), 340–41.

- 13. See Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 782–785, 805–812.

- 14. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 797–798.

- 15. See Matthew Roper, “‘A Key That Will Never Rust’: The Majority of the Church Will Never Be Led Astray,” Ether’s Cave (blog), 20 October 2014 for a compilation of sources regarding how early leaders of the Church taught that the majority would not be led astray due to the law of common consent established in the Doctrine and Covenants. For a summary of this meeting, see Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 789–99; Walker, “Six Days in August: Brigham Young and the Succession,” 174–88.

- 16. This would necessitate Sidney’s being excommunicated a month later. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 812–24.

- 17. For many of these accounts, see Lynne Watkins Jorgensen, “The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Psses to Brother Brigham” One Hundred Twenty-one Testimonies of a Collective Spiritual Witness” and “Documents of Testimonies of the Mantle Experience,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820-1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed. (BYU Studies, 2017), 373-480.

- 18. See Jorgensen, “The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Passes to Brother Brigham: One Hundred Twenty-nine Testimonies of a Collective Spiritual Witness,” 404–5.

- 19. For an in-depth analysis of this event, see Lynne Watkins Jorgensen, “The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Passes to Brother Brigham: One Hundred Twenty-nine Testimonies of a Collective Spiritual Witness,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820-1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed. (BYU Studies, 2017), 394–429. Although many of the accounts were written years after the event, they were passed on through familial oral tradition. Given the sheer volume of witnesses and the consistency between the accounts, it is difficult to ignore the evidence for this miracle without engaging in special pleading, as some historians who are both antagonistic to the Church and who reject this miracle often resort to.

- 20. “Documents of Testimonies of the Mantle Experience,” 474.

- 21. Hickenlooper’s letter, as well as his son-in-law’s response, were printed in “Correspondence, G.S.L. City, UT, May 25, 1855,” Northern Islander 5, no. 8 (August 16, 1855). According to Hickenlooper, “The first evidence I received that Brigham was the true successor of Joseph, was on the day when Sidney [Rigdon] set up his claim for the presidency. Brigham’s countenance his voice, gestures and everything truly represented the martyred prophet in such a striking manner I shall never forget—I was convinced by the spirit of the Lord that the mantle of Joseph had fallen on Brigham.” His son-in-law, in response, claimed Brigham had been actively trying to mimic Joseph in appearance and sound, even falsely asserting that Brigham had a tooth removed to be able to mimic Joseph’s voice. This response shows that rather than denying a miracle had happened, some who followed other false prophets after Joseph’s death were aware that something had happened and had to explain it away.

- 22. For an overview of these individuals, see R. Jean Addams, “Aftermath of the Martyrdom: Aspirants to the Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” in Joseph Smith: A Life Lived in Crescendo, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2024), 977–1050.

- 23. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 746.

- 24. For an excellent discussion on how the introduction of temples and temple ordinances connects to the 1844 succession crisis, see Andrew F. Ehat, Joseph Smith’s Introduction of Temple Ordinances and the 1844 Mormon Succession Question (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1982).

- 25. “Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846; Volume 1, 10 March 1844–1 March 1845,” pp. 382–83, The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 26. “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons 5, no. 19 (October 16, 1844): 683.

- 27. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 747.

- 28. Esplin, “Authority, Keys, and ‘the Measures of Joseph,’” 839.