KnoWhy #820 | October 23, 2025

Why Did Joseph Smith Publish the Book of Abraham Just Prior to Revealing the Temple Endowment?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Come ye, with all your gold, and your silver, and your precious stones, and with all your antiquities; and with all who have knowledge of antiquities, ... and build a house to my name, for the Most High to dwell therein. Doctrine and Covenants 124:26–27

The Know

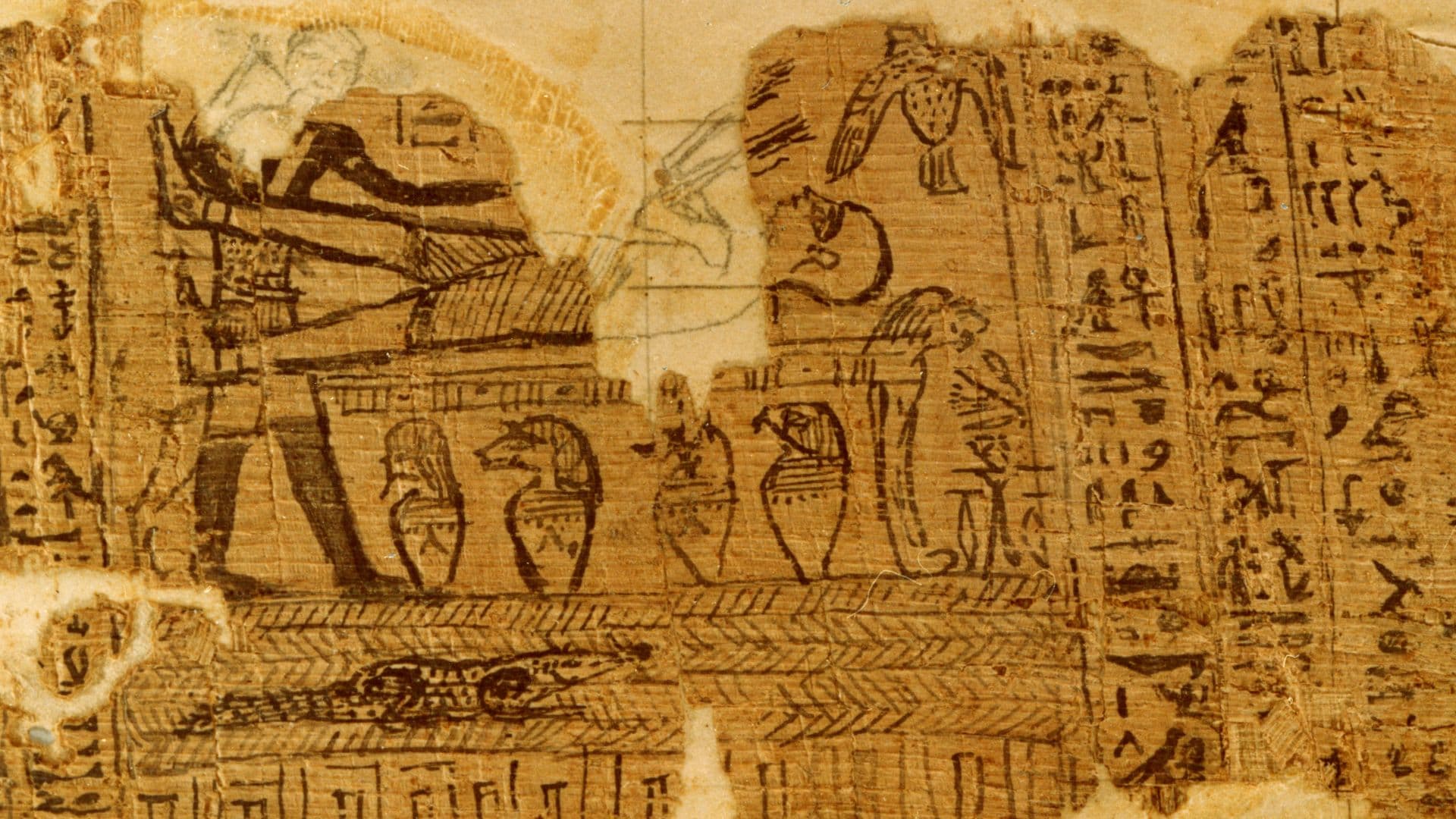

Joseph Smith introduced the temple endowment ceremony to nine leaders of the Church in Nauvoo on May 4, 1842.1 In the spring leading up to that date, the Prophet was engaged in various activities and experiences that prepared him and others for the sacred rite.2 One such activity was his final effort to translate and publish the Book of Abraham, which Joseph claimed was written on some Egyptian papyri that he had obtained.3 The text of the Book of Abraham, along with facsimile copies of three illustrations the Prophet had gathered from various other papyri, were published in the Times and Seasons starting on March 1, 1842.4

Scholars have noted that the publication of this record and the introduction of the endowment ceremony appear to be related. According to Andrew Ehat, “Joseph’s publication of the Book of Abraham two months before the endowment ordinances were first given included allusions” to that ceremony.5 John Gee stated,

It may not be coincidence that Joseph Smith began translating the Book of Abraham just before the dedication of the Kirtland Temple and the introduction of some temple ordinances at that time, and that he published the excerpts we now have of the Book of Abraham just before he introduced the temple endowment in Nauvoo. The Book of Abraham thus serves, in a way, as an introduction to the ordinances of the temple and the covenants made there.6

Terryl Givens has offered a similar conclusion:

These sacramental rites in Smith’s temple project followed immediately on the heels of his translation and publication of the bulk of the Book of Abraham [in March 1842]. For it was the Book of Abraham that served to complete the picture of this heavenly chain that it was his task to reconstitute. This grand theological project and the role the Book of Abraham was made to play in Smith’s temple theology explain the significance of this scripture in Latter-day Saint thought. We can best understand the import of the Abrahamic narrative Smith reconstructs within the actual plenitude of the temple theology toward which all his labors were directed.7

The following explanations offer several specific concepts, themes, and progressions appearing in the Book of Abraham that likely helped the Saints prepare or understand the temple ceremony the Prophet was about to reveal:

- The three facsimiles of Egyptian images the Prophet attached to the Book of Abraham not only were adapted to illustrate the story of Abraham’s life but also portray the general progression of elements found in ancient temples. They show that Abraham’s life can be viewed as a sacred journey or initiation, as was understood even in antiquity. For example, Philo of Alexandria observed, “The journey of Abraham from Chaldaea is a symbol of the soul leaving behind the realm of sense-perception and mortal existence to seek God . . . he migrated from the world of idols to become initiated in the sacred learning of the one God.”8 In particular:

- Joseph Smith interpreted facsimile 1 as Abraham’s altar of self-sacrifice described in chapter 1. Such an altar corresponds to the sacrificial altars in temple courtyards, where preparations for entering temples were made.9 This aligns with the altar of sacrifice in the beginning stages of the temple endowment.10

- Moreover, Joseph interpreted facsimile 2 in relation to Abraham’s cosmic vision in chapters 3–5. According to John Welch and Michael Rhodes, the sequential numbering of the specific elements in facsimile 2 suggests that Joseph was interpreting that image as a progressive journey from the pre-mortal presence of God (represented by Kolob), beginning at the center (with figure 1) and progressing through a series of stages, involving an altar and also key words and a sign, and finally returning as glorified beings with solar disks above their heads (see figures 22 and 23) back into the presence of God in the center.11 This corresponds well with the cosmic visions and themes of heavenly ascent that ancient texts associated with entering temple precincts. It also aligns with the entire progression of the Nauvoo endowment ceremony, which began with God and a heavenly council prior to Creation and ended back in the presence of God, including signs and key words along the way. Joseph Smith even said that the understanding of some elements in facsimile 2 was only “to be had in the Holy Temple of God” (see figure 8). This directly connects this facsimile—and likely, by extension, the other two facsimiles as well—to instructions, rites and ordinances given in the holy temple. Interestingly, even though Joseph Smith didn’t provide the explicit translated meaning of several portions of facsimile 2 (especially the texts designated as figures 8–21), the corresponding hieroglyphic inscriptions indeed can be related to several ancient Egyptian contexts.12

- And finally, facsimile 3 with its six explanatory comments, published separately two months later, on May 16, 1842, portrays Abraham’s ascension to a royal throne, upon which he can be seen “reasoning on the principles of Astronomy in the king’s court.”13 Much of this royal enthronement imagery corresponds well with elements found in the inner-most part of Israelite temples, referred to as the Holy of Holies. It also aligns with symbolically entering into the presence of God in the celestial room, as presented in the Nauvoo temple endowment ceremony.

- In the text of the Book of Abraham, the ancient patriarch tells how he left behind the idolatry of his fathers, “having been myself a follower of righteousness, desiring also to be one who possessed great knowledge.” He also describes wanting to be “a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge . . . and desiring to receive instructions” on his way to “greater happiness and peace and rest.” Abraham further tells how God promised him these blessings in connection with a covenantal relationship (Abraham 1:2, 2:6–13). For Latter-day Saints, this offers a model of how to seek and receive the covenantal blessings in the temple endowment ceremony that was about to be revealed. Initiates would be called upon to progress from the righteousness they had already attained to even greater, higher, and holier forms of devotion through a progressive covenantal relationship with God.

- The Book of Abraham emphasizes that the patriarch’s quest for happiness and peace was wrapped up in his obtaining a high priesthood (Abraham 1:2, 31). As Terryl Givens noted, “This right to the priesthood, in fact, and not promised land or unspecified blessings to dispense upon posterity, is identified as the essence of Abraham’s inheritance in Smith’s revised version of the covenant God makes with him.”14 This parallels the endowment ceremony and temple ordinances as a whole, which Joseph Smith revealed as initiations into various priestly orders, culminating in the high priesthood.

- Abraham’s vision of the cosmos included a remarkable vision of the premortal existence of man and a divine council of gods (Abraham 3–5). These concepts were likewise integral to the Nauvoo temple endowment ceremony.

- God’s promise that Abraham would have posterity—both natural and adopted—that would become a nation and be as numerous as the stars provided a doctrinal foundation for temple sealings and eternal families (Abraham 2:9–10; 3:14).

These and several other correlations suggest that the Book of Abraham was published in the spring of 1842 not just as new scripture but also as a revelatory springboard to introduce the Saints to the higher knowledge and sacred rituals the Nauvoo temple endowment ceremony would soon convey.

The Why

Just as the Book of Moses had prepared the Saints in Kirtland for earlier temple teachings and initiatory ordinances in 1836, the Book of Abraham functioned in Nauvoo as a revelatory text that opened new vistas of knowledge in preparation for the unfolding of the temple endowment in 1842. David Calabro insightfully declared that a “ritual reading of the Book of Abraham helps to place the book in the historical context of the Restoration as a follow-up to the Book of Moses and a prelude to the temple endowment.”15

For the Prophet Joseph Smith, translating Abraham’s story offered inspiration and a divine model that guided him as he unfolded the sacred temple rites for the Nauvoo Temple. For Latter-day Saints then and now, the Book of Abraham’s emphasis on obtaining blessings—including entering the holy order of the priesthood, creating a covenantal relationship with God, forging connection with one’s posterity, and gaining knowledge of cosmic purpose through heavenly visions or instruction—provides an eternal covenantal framework and profoundly inspiring meaning that undergirded the temple endowment Joseph Smith unfolded in 1842.

Additionally, several thematic elements in the Book of Abraham help Latter-day Saints understand that their current covenantal blessings and obligations and knowledge of the plan of salvation, as revealed by Joseph Smith through the temple, stretch back to Abraham and beyond. This helps people receiving the temple endowment today to know that they are a part of something grand—an enterprise of epic proportions—that provides the divine strength needed to endure the challenges they face.

Finally, Abraham’s experience provides an example of how one can personally progress through the covenants of the temple. Through the Lord’s help, Abraham escaped from the wicked idolatry of his day, received profound revelations that helped him find meaning and purpose in his life, and then lived faithfully to see the fulfillment of God’s promised blessings. All who model their lives accordingly are assured that, through the love and atoning power of Jesus Christ, they will become “the seed of Abraham, and the church and kingdom, and the elect of God” (Doctrine and Covenants 84:34).

John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017).

Stephen O. Smoot, “Temple Themes in the Book of Abraham,” in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 60 (2024): 211–38.

John W. Welch and Michael D. Rhodes, “Approaching Eternal Life: Temple Elements by the Numbers in Facsimile 2,” in Abraham and His Family in Scripture, History, and Tradition: Proceedings of the Conference Held May 3 & 10, 2025, at Brigham Young University, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John S. Thompson, Matthew L. Bowen, and David R. Seely (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2025), 23–97.

- 1. The May 4, 1842, entry in Joseph Smith’s journal briefly mentions the initial giving of the endowment ceremony, referring to it as “certain instructions concerning the priesthood.” “Journal, December 1841–December 1842,” p. 94, The Joseph Smith Papers. The entry for this date in the 1838 History of the Church provides more detail. See “History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842],” p. 1328, The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 2. On Joseph Smith’s experiences with Freemasonry in the spring of 1842 and its limited relationship to the Nauvoo endowment ceremony, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Freemasonry and the Origins of Latter-day Saint Temple Ordinances (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2022). Joseph Smith’s initial teachings to the Relief Society, organized in March of 1842, reveal that one large purpose for its organization was to prepare the sisters and the Saints for the temple. See Scripture Central, “Why Was the Relief Society Organized? (Doctrine and Covenants 124:55),” KnoWhy 819 (October 21, 2025). Prior to these spring 1842 preparations, earlier events can also be considered preparations for the much later Nauvoo endowment ceremony: Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon with its temple building, sermons, and covenant making; the restoration of priestly offices of the temple, such as priest and high priest; and the revisions and expansions of the Bible in the early 1830s, containing temple-centric ideas such as washing, heavenly ascent, and cosmic visions.

- 3. The introductory paragraph for the text Joseph Smith published states that the text was “a translation of some ancient records that have fallen into our hands, from the catacombs of Egypt, purporting to the writings of Abraham . . . upon papyrus.” “Book of Abraham and Facsimiles, 1 March–16 May 1842,” p. 704, The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 4. See “Introduction to Facsimile Printing Plates and Published Book of Abraham, circa 23 February–circa 16 May 1842,” The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 5. Andrew Ehat, “Joseph Smith’s Introduction of Temple Ordinances and the 1844 Mormon Succession Questions” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1981), 43.

- 6. John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 165–66.

- 7. Terryl Givens, The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism’s Most Controversial Scripture (Oxford University Press, 2019), 124–25, Kindle.

- 8. Philo, De Migratione Abrahami (Loeb Classical Library), 254–59, especially §6.

- 9. On the construction and purposes of sacrificial altars in courtyard, see Exodus 27:1–8; 29:10–46; 38:1–7; Leviticus 1–7, 9; 1 Kings 8:64; 2 Chronicles 4:1; and Ezra 3:2–6. Note that in Abraham 1:10, Abraham’s altar “stood by the hill called Potiphar’s Hill,” suggesting it was part of a cult complex with the altar in a courtyard “by” or next to a temple structure represented by the hill.

- 10. For a study on the layout of the Nauvoo temple ceremony, including altars, see Lisle G. Brown, “The Sacred Departments for Temple Work in Nauvoo: The Assembly Room and the Council Chamber,” BYU Studies 19, no. 3 (1979): 361–74. See also Don F. Colvin, “Interior Features,” in Nauvoo Temple: A Story of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University 2002), 179–232.

- 11. John W. Welch and Michael D. Rhodes, “Approaching Eternal Life: Temple Elements by the Numbers in Facsimile 2,” in Abraham and His Family in Scripture, History, and Tradition: Proceedings of the Conference Held May 3 and 10, 2025 at Brigham Young University, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John S. Thompson, Matthew L. Bowen, and David R. Seely (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2025), 23–97.

- 12. On the general relationship between facsimile 2 and the temple, see Hugh W. Nibley and Michael D. Rhodes, One Eternal Round (Deseret Book, 2010). On the relationship between figure 8 and the temple specifically, see Stephen O. Smoot, “Temple Themes in the Book of Abraham,” in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 60 (2024): 229–36. John S. Thompson, “‘We May Not Understand Our Words’: The Book of Abraham and the Concept of Translation in The Pearl of Greatest Price,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 41 (2020): 20–24, suggests that Joseph Smith did not translate the texts in the facsimiles because his purpose was not to restore ancient Egyptian religion, to which these texts are specifically tied. However, the images were used because Joseph Smith could interpret them to convey broader ideas related to the Abrahamic religion that he was seeking to restore.

- 13. See the explanations to facsimile 3.

- 14. Givens, Pearl of Greatest Price, 122.

- 15. David Calabro, “The Choreography of Genesis: The Book of Abraham as a Ritual Text,” in Sacred Time, Sacred Space, and Sacred Meaning: Proceedings of the Third Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, 5 November 2016, Temple on Mount Zion 4, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2020), 241–61.